Gina Sideli, assistant professor of plant biology, works in the blueberry fields at the Philip E. Marucci Center for Blueberry and Cranberry Research. Nick Romanenko/Rutgers University.

Research to find a new variety enters its final phase this summer

Rutgers researchers are getting close to identifying a new blueberry variety that can produce a sweeter, firmer fruit for Garden State growers.

The decade-long research project will move into its final trial this season. Of the thousands of blueberry plants evaluated for desirable traits at Rutgers’ Philip E. Marucci Center for Blueberry and Cranberry Research and Extension in Chatsworth, NJ, only three or four samples will be selected to move forward, said Gina Sideli, who is an assistant professor of plant biology at the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences and directs the center’s breeding program.

When that trial culminates in about five years, Rutgers hopes to have a new and improved blueberry cultivar to bring to market. The state produces between 35 and 45 million pounds of blueberries on average a year to serve the densely populated Northeast.

“Of course, the growers want it yesterday,” said Sideli, who explained there hasn’t been a new blueberry cultivar developed for this market in about 30 years. “It’s a huge investment to plant and replant fields and a big risk for them to experiment with a new cultivar.”

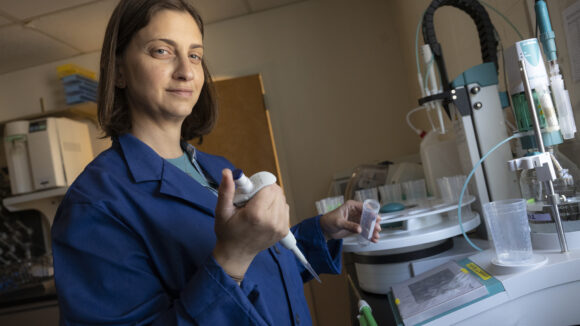

Gina Sideli in the chemistry lab at the Philip E. Marucci Center for Blueberry and Cranberry Research. Nick Romanenko/Rutgers University

Fourth-generation farmer Brandon Raso, part-owner of Variety Farms in Hammonton, NJ, grows 750 acres of blueberries, including the 30-year-old Duke varietal and 70-year-old Blue Crop varietal, which are just about ripe for harvest. He said Rutgers’ blueberry research will take the guesswork out of which new and improved varietal to invest in.

“An acre of blueberries costs about $12,000 to $15,000 planted. We do trials of 10 acres, so that’s upwards of $120,000,” he said. “For the grower to eat that cost time after time, it’s not sustainable. That’s why Rutgers is pivotal.”

A new blueberry cultivar proven to yield a less-tart-tasting, firmer fruit could mean significant economic benefits for local growers who are trying to cater to ever-changing consumer tastes.

“Consumers don’t want tart sour flavor, they want a sweeter, larger berry that’s going to have a better shelf life, so it won’t rot in a few days,” Sideli said.

This is a top priority for Raso, who said consumers have become accustomed to the unblemished berries flooding supermarkets from South America and Mexico in recent years.

“When the Blue Crop variety came out in the ’50s, quality standards were almost nonexistent,” he said. “Now consumers are more selective.”

Growers from South America and Mexico are new to the industry and present a windfall to private breeders looking to supplement expanding markets. Those growers are reaping the benefits of new research that is targeted to their regions to produce longer-lasting fruit that can withstand travel to markets.

“Because the focus has been on creating the ultimate berry for those guys and they successfully have done it, North American guys, specifically in New Jersey, are left with some of the older varietals that maybe don’t yield as much or are as firm,” he said.

Gina Sideli walks through the blueberry fields at the Philip E. Marucci Center for Blueberry and Cranberry Research. Nick Romanenko/Rutgers University

Berries that ripen more evenly on the bush and are less susceptible to bruising will also allow more local growers to consider making the switch from hand harvesting to machine harvesting, said Raso, which is more cost effective and efficient.

“Fifteen years ago, we would employee 1,000 seasonal laborers, now we’re lucky to get 350,” he said. “To make up for that difference in labor, mechanical harvesting is the easy answer.”

Today Raso estimates his farm, started by his maternal great-grandfather in 1928, does the most machine blueberry harvesting in the state.

While machine harvesting is fast and cuts down on labor costs, it does result in crop loss, with about 35 percent of the berries landing on the ground instead of on the conveyor belts. His hope is that the Rutgers trial results in a sturdy plant that is the right height for harvesters and produces a good quantity of firm, sweeter berries.

Regardless of whether that new cultivar turns out to be a Rutgers-produced varietal, or one from a private breeder, Sideli said the state’s blueberry growers will benefit in the end.

“What we want to do at the center is get some of these new cultivars from private breeders, run trials and have that information available to the growers so they can make a more educated decision,” she said. “We are still trying to make the next best available to New Jersey growers – whether it’s Rutgers’ or not.”

This article originally appeared in Rutgers Today.