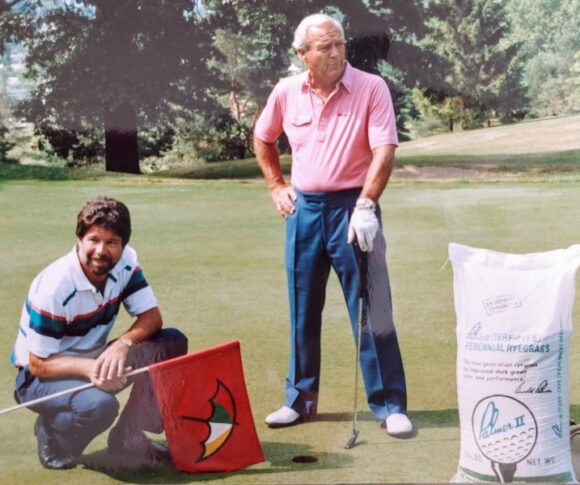

Richard Hurley GSNB’83 at the East Coast Sod & Feed farm in Salem County, New Jersey, with a bucket of turfgrass seed he developed. Courtesy of Rutgers University Foundation.

New Jersey native and Rutgers turfgrass PhD alumnus Richard Hurley has been a leader in breeding grasses used on golf courses around the world, ranging everywhere from Australia to the Masters, which is hosted each year in Georgia. For decades, the iconic Augusta National Golf Club has used cool-season grasses developed at Rutgers.

Richard Hurley was a golf course superintendent at a prestigious South Jersey country club when an appealing proposition came his way. The owner of the Loft’s Seed company in Bound Brook, New Jersey, told him, “I’d like you to come to work for me, and then I would like you to go to Rutgers University and study under Dr. Reed Funk to get your PhD in grass breeding.”

Hurley couldn’t pass up the 1978 offer to serve as Peter Loft’s director of research, which also included the company paying his Rutgers tuition. Funk, a pioneer in the science of turfgrass, led the program.

“Dr. Funk developed all the practices and procedures that we still do today,” says Hurley, who graduated with a doctorate in 1983 in soils and crops and went on to an exceptional career that includes developing grasses used everywhere from the Olympics to the White House putting green. “He passed away 12 years ago, but his footprint is still there. We still use his teaching, his training, his concepts, his procedures.

Hurley in the mid-80s with Arnold Palmer, a longtime friend and turfgrass business partner.

Hurley, 77, remained close to Funk after graduating and collaborated with him on developing grasses. “He was such a generous person with his knowledge,” he says. “If I hadn’t had that opportunity, my life would be very different.”

Hurley went to teach numerous classes in what is now known as the Rutgers Center for Turfgrass Science, where students called him “Doc Hurley.” He mentored many as he was mentored, including those attending the Professional Golf Turf Management School. “I wouldn’t say you can’t succeed without mentors, but certainly it makes life a lot easier,” he says. “In my life, Dr. Funk certainly is right there as one of the most important.”

The Masters

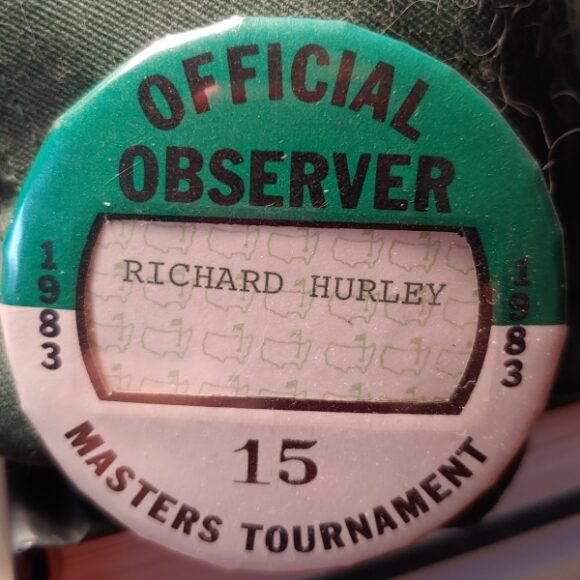

Hurley’s new job as Loft’s Seed’s director of research came with an invitation that golfers and greenskeepers alike covet—the opportunity to attend the Masters and work on the course at the hallowed Augusta National Golf Club. “I was immediately put on the agronomic consulting team at Augusta,” Hurley says.

Hurley’s Masters badge from the year he earned his Rutgers PhD.

Forty-six years later, Hurley, who first attended the Masters in 1973 before beginning his streak in 1978, has not missed the annual tournament. Although he has attended as a spectator for the past 15 years, he worked as an adviser on the Augusta National course from 1978–1993, a transformative time in golf course maintenance as technology improved. “They went from old school to high tech irrigation practices—everything was enhanced and improved,” he says. “They wanted the best.”

Prior to Hurley’s arrival, Rutgers had long been a primary influence on Augusta National’s breathtaking greenness, using variants of the cool-season perennial ryegrasses first developed by Funk at the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station. Those grasses do better in early spring, supplementing Augusta’s traditional Bermuda turf, which is more common on courses in warmer climates. “The famous wall-to-wall green color on display at Augusta National wouldn’t be possible without improved perennial ryegrass cultivars, the first of which was released in 1967,” says an article in the Golf Course Superintendents Association magazine that cites Funk as the first developer.

After serving as an Augusta National adviser, Hurley worked another 15 years on the course’s volunteer greenskeeper team. He often was assigned during play to tend to the 12th hole, which is known as Golden Bell and is famous for the scenic, stone Hogan Bridge crossing Rae’s Creek. A primary job was keeping the green pristine between tee shots with a “whipping stick”—a long rod that wipes the surface clean—and a backpack blower.

In 2008, he “retired” from tournament support after 30 years of service and was awarded two lifetime passes, known as “patron’s badges” in the persnickety parlance of the Masters. “Traveling to Augusta each year to attend the Masters makes me feel like Augusta is my home, at least for one week of the year,” says Hurley, who has lived in the Orlando area since 2014.

From the Jersey Shore to Golf Courses Worldwide

Hurley grew up in Neptune on the Jersey Shore, right across the street from what was then the Asbury Park Golf Course, now the Shark River Golf Course in the Monmouth County Park System. He caddied there as teenager at a professional event for two pioneering Black players, Charlie Sifford and Lee Elder, who went on to lead integration of the professional golf ranks. “That was my real start of being around the golf course,” he says. “That’s where I learned how to play golf.

He pursued degrees in turf management, first at a two-year college in Miami and then at the University of Rhode Island, where he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees. Prior to enrolling at Rutgers and joining Loft’s Seed, he served as golf course superintendent at Tavistock Country Club in Haddonfield, New Jersey.

Since graduating in 1983, his career has included developing and releasing many widely used and popular golf course grasses, earning him the moniker “the bentgrass doctor.” High-profile projects include a partnership for grass branded with Arnold Palmer’s name that developed into a long friendship. “Arnold certainly was ‘The King,’ and I got to know him quite well,” Hurley says.

Hurley later helped to develop the Rutgers-bred 007 creeping bentgrass that was used at the Tokyo 2020 Olympics. He has since developed additional versions of the 007 grass—so named not for James Bond, but because it was released in 2007.

Hurley at the New South Wales Golf Club in Sydney, Australia, which is using Hurley’s 777 bentgrass, another variety developed with Rutgers collaboration.

He has been an influence on golf courses in Japan and Australia, where more than 600 courses use grasses he and Rutgers associates developed, as well as Russia, England, Ireland, and South Africa. When Bill Clinton wanted to reinstate the White House putting green that Dwight D. Eisenhower had once used, the famed golf architect Robert Trent Jones Jr. tapped Hurley to do the job.

Hurley says his accomplished career would not have been possible without his association with Rutgers. “The turf breeding program at Rutgers is so unique,” says Hurley. “It’s the largest cool-season turfgrass breeding program in the world, and it’s very productive. And today you’ve got a tremendous staff there that is continuing Dr. Funk’s work.”

Hurley worked closely with fellow Rutgers alumnus Bruce Clarke, an extension specialist in turfgrass pathology, who retired in 2022 after almost 40 years with the turfgrass program. A scholarship fund named for Clarke CC’77, GSNB’82, supports graduate fellowships.

This article first appeared on the Rutgers University Foundation website.