Gediminas Mainelis, a professor in the Department of Environmental Science, has been studying nanoparticles since 2012.

Common household products containing nanoparticles – grains of engineered material so miniscule they are invisible to the eye – could be contributing to a new form of indoor air pollution, according to a Rutgers study.

In a study published in the journal Science of the Total Environment, a team of Rutgers researchers found people walking through a space, where a consumer product containing nanoparticles was recently sprayed, stirred residual specks off carpet fibers and floor surfaces, projecting them some three to five feet in the air. A child playing on the floor nearby would be more greatly affected than the adult, experiments showed.

“If an adult is walking in a room, and steps on some of these deposited particles, we found that the particles will be re-suspended in the air and rise as high as that person’s breathing zone,” said Gediminas Mainelis, a professor in the Department of Environmental Science at Rutgers School of Environmental and Biological Sciences, who led the study. “A child playing on the floor inhales even more because the concentrations of particles are greater closer to the ground.”

While it’s still too early to gauge the long-term effects of these particles on people’s health, Mainelis said the results are important to contemplate. “At this point, it’s more about increasing awareness so that people know just what they are using,” he said.

A nanoparticle is a fleck of material ranging in size approximately between 1 and 100 nanometers. A nanometer is one-billionth of a meter. The human eye only can see particles larger than ~50,000 nanometers. A sheet of office paper is about 100,000 nanometers thick.

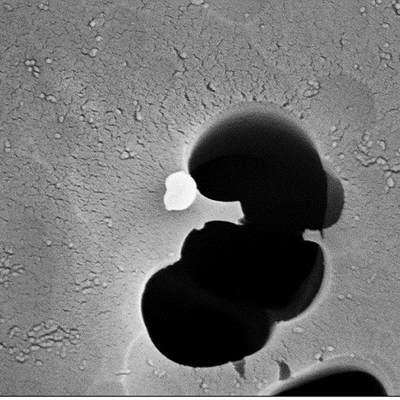

The Mainelis research team collected this re-suspended silver nanoparticle on a filter during an experiment. Photo:

Mainelis Lab.

Nanoparticles are in a wide range of popular household products such as cleaners, disinfectants, sunscreen, hairsprays, and cosmetic mists and powders.

Nanomaterials, often made from silver, copper or zinc, have become widely used in industry because of the unusual properties they exhibit when manipulated on a microscopic level.

Scientists have found particles altered at the “nanoscale” can differ in important ways from the properties exhibited by the material in bulk. Some nanoparticles are stronger or have different magnetic properties compared with other forms or sizes of the same material. They can conduct heat or electricity more efficiently. They’ve been found to become more chemically reactive, reflect light better or change color.

Since nanoparticles differ substantially from the properties of the same material in aggregated form, researchers worry that nanoparticles may differ in terms of being more strongly toxic, with consequences for human health.

“There is very limited knowledge of the potential for exposure to nanoparticles from consumer products and resulting health effects,” said Mainelis, who has been studying these substances since 2012.

Scientists have long been familiar with the fact that pollutant particles deposited on flooring surfaces could be resuspended by walking, Mainelis said. What wasn’t known was whether particles from nanotechnology-enabled consumer sprays could be resuspended. Also, the factors affecting resuspension weren’t well understood.

To learn more, Mainelis and his team constructed an enclosed, air-controlled chamber in a section of his laboratory with both carpeting and vinyl flooring. They used a small robot to simulate the actions of a child. And, wearing Tyvek suits and respirators, they walked the surface after seven products containing nanoparticles of silver, zinc, and copper were sprayed into the air, and measured the results.

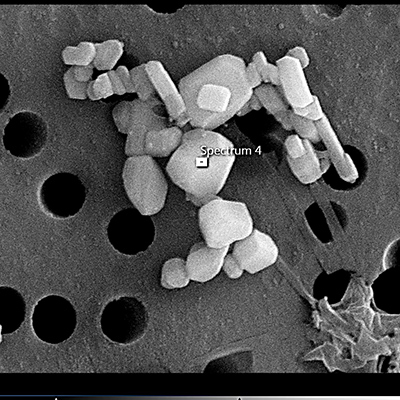

Nanoparticles tend to clump together, as seen in this image of zinc particles taken with a scanning electron microscopy. Photo: Mainelis Lab.

They confirmed nanoparticles were released by the tested sprays and reached the human breathing zone. They found children could be exposed to higher particle mass concentrations than adults during spraying and resuspension of deposited particles. The study also showed resuspension of particles from carpets produced a higher concentration of particles than from the vinyl flooring. The researchers also concluded that the concentration of particles resuspended by their motion depended on the product.

The research can guide individuals on approaches to protect health, Mainelis said.

“We can use this knowledge to minimize our exposures, in this case to various nanomaterials,” Mainelis said. “Overall, this work could help us understand the resulting exposures and support future studies on human exposure reduction.”

Other researchers on the study included Jie McAtee, a postdoctoral associate, and Ruikang He, a doctoral student who graduated in 2023 and is now a postdoctoral associate in China, both in the Department of Environmental Science at the Rutgers School of Environmental and Biological Sciences.

This article first appeared in Rutgers Today.