Bottom-dwelling fish such as Atlantic cod are often found near structures such as shipwrecks. Photo: NOAA.

Study suggests reducing fishing and addressing environmental changes would help cod recover

Overfishing likely did not cause the Atlantic cod, an iconic species, to evolve genetically and mature earlier, according to a study led by Rutgers University and the University of Oslo – the first of its kind – with major implications for ocean conservation.

“Evolution has been used in part as an excuse for why cod and other species have not recovered from overfishing,” said first author Malin L. Pinsky, an associate professor in the Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Natural Resources in the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences at Rutgers University–New Brunswick. “Our findings suggest instead that more attention to reducing fishing and addressing other environmental changes, including climate change, will be important for allowing recovery. We can’t use evolution as a scapegoat for avoiding the hard work that would allow cod to recover.”

The study, which focuses on Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) off Newfoundland in Canada and off Norway, appears in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

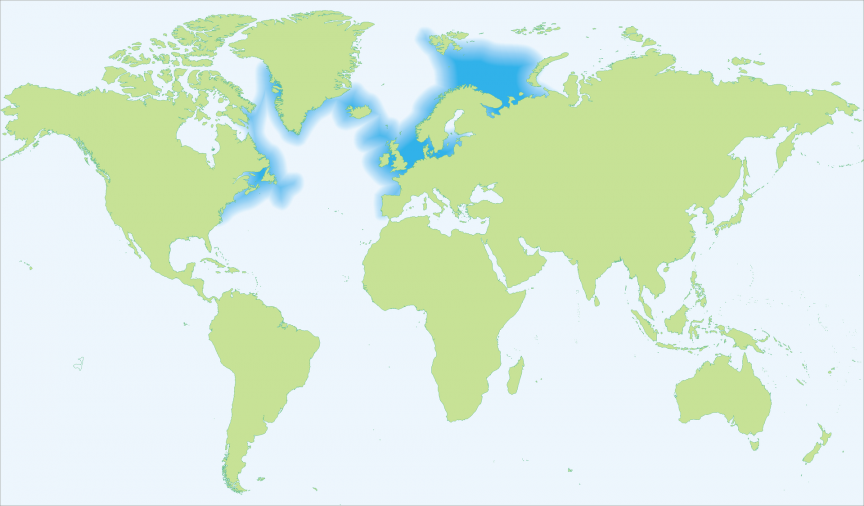

In the Northwest Atlantic Ocean, cod range from Greenland to Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. In U.S. waters, cod is most common on Georges Bank and in the western Gulf of Maine, but both fish stocks are overfished. Cod can reach 51 inches long, weigh up to 77 pounds and live more than 20 years. Early explorers named Cape Cod in Massachusetts for the species because it was so abundant off New England, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Atlantic cod habitat includes both sides of the north Atlantic Ocean and beyond. Image: NOAA.

Many debates over the last few decades have centered on whether cod have evolved in response to fisheries, a phenomenon known as fisheries-induced evolution. Cod now mature at a much earlier age, for example. The concern has been that if the fish have evolved, they may not be able to recover even if fishing is reduced, according to Pinsky.

Cod populations with late-maturing individuals can produce more offspring and more effectively avoid predators, he said. They are also better protected against climate variability, more stable and less likely to collapse.

Both theory and experiments suggest that fishing can lead to an earlier maturation age. But prior to the new study, no one had tried to sequence whole genomes from before intensive fishing to determine whether evolution had occurred. So, scientists sequenced cod earbones and scales from 1907 in Norway, 1940 in Canada and modern cod from the same populations. The northern Canadian population of cod collapsed from overfishing in the early 1990s, while the northeast Arctic population near Norway faced high fishing rates but smaller declines, the study says.

“We found that cod likely did not evolve in response to fisheries,” Pinsky said. “There were no major losses in genetic diversity and no major changes that suggested intensive fishing induced evolution. We cannot entirely rule out that evolution happened, but it’s more likely that the fish are developing earlier as a response to their environment and would be able to develop and mature later if the environment changes, benefiting the species.”

The scientists’ findings complement conclusions from literature reviews and evolutionary modeling that the direct impacts of fisheries on populations and ecosystems are a more pressing concern than the effects of fisheries-induced evolution, the study says. Avoiding overfishing and reducing fishing pressure when populations become low remain a key management strategy.

“A big question is whether other species, especially those with shorter lifespans, may show signs of evolution, in contrast to the long-lived cod,” Pinsky said. “We are investigating this by DNA sequencing 100-year-old specimens from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.”

Scientists at the University of Oslo, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Institute of Marine Research (Norway), University of Basel and University of Zurich contributed to the study.

This article first appeared in Rutgers Today.