When it comes to produce, New Jersey is among the top 10 producers nationally of several crops, including tomatoes ($47.3 million production value).

This article first appeared in NJ Biz.

The basics:

- Agriculture is New Jersey’s third-largest industry, generating approximately $1.5 billion in annual revenue.

- The industry is facing challenges such as a tough regulatory environment, high operating costs, competition and unpredictable weather conditions.

- Small and mid-sized farms around the state are embracing agritourism as a means to add value to their products and attract consumers.

New Jersey has a lot on its plate.

With nearly 10,000 farms spread across 750,000 acres, this state produces more than 100 different kinds of fruits and vegetables, from cranberries and peaches to cucumbers and asparagus. After pharmaceuticals and tourism, agriculture is the state’s largest industry, bringing in roughly $1.5 billion in revenue annually, helping New Jersey live up to its “Garden State” nickname.

“Yes, we’re a big industrial state and big in financial services, but agriculture is a very important part of our economy and a very important part of our local economies,” said Brian Schilling, director of the Rutgers Cooperative Extension and senior associate director of the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station. “It’s also an important part of our landscape, our quality of life and heritage. There are so many benefits of having a local agriculture in New Jersey.”

Despite facing numerous challenges – from a tough regulatory environment to high costs of doing business – Schilling said the state’s farms are “still going strong” thanks to the industry’s efforts to constantly innovate.

“You can’t just ignore the realities around you, whether it be climate pressures or market changes,” he said. “I know folks that used to farm 1,500 acres, but that land has been slowly sold for development – warehouses in many cases – and they’re now down to 800 acres. So, they’ve moved into agritourism, direct marketing or diversified crops as a way to adapt.”

New Jersey Assistant Secretary of Agriculture Joe Atchison III highlighted just a few of the factors that contribute to the industry’s strength. “While the soils in the south may be suited for a particular crop (blueberries in Atlantic County for example), the soils in the north can support different types of produce. It’s what makes the Garden State such a unique player in the agricultural industry. Also, New Jersey is within less than six hours of 50 million consumers along the Eastern seaboard, meaning food that is picked that morning can be on the tables of those consumers in less than a day, giving New Jersey growers an advantage over many other states,” he said.

Atchison also pointed to the success of Jersey Fresh, which is the longest running state agriculture marketing brand in the U.S., having been in place since 1984.

“If a consumer sees the Jersey Fresh brand, they know they are getting produce picked at the peak of freshness. Jersey Fresh is known across the country for the quality it has consistently delivered over the years, allowing our growers a large market for them to sell their produce. From the success of the Jersey Fresh program, the State has developed Jersey Seafood, Jersey Raised (livestock) and Jersey Grown (horticultural products),” he said.

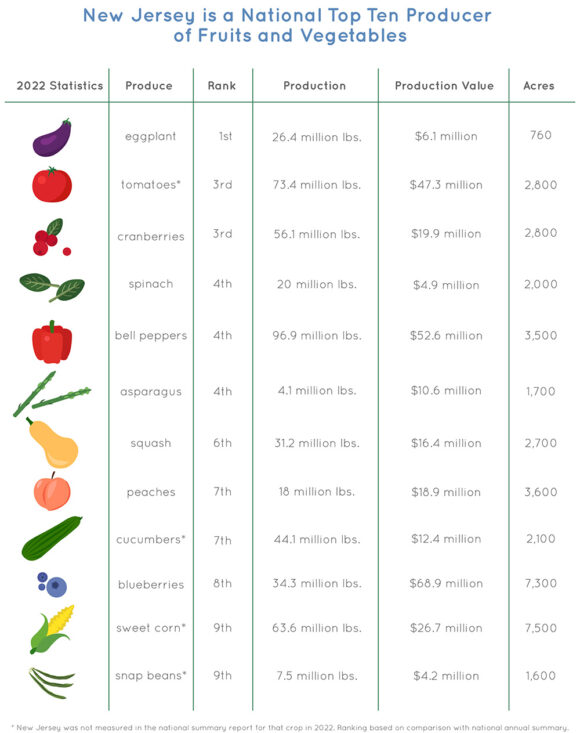

New Jersey is a national top 10 producer of fruits and vegetables.

Overall, New Jersey’s agriculture economy continues to be led by horticulture, which consists of nursery and greenhouse products, sod and Christmas trees, with annual sales of almost $500 million.

Seafood is also a valuable commodity, with tons of bluefish, sea scallops, blue crabs, surf clams, flounder, shellfish and other species harvested annually. Sold here at home, as well as in foreign markets around the world, the state’s commercial fishing industry tacks on another $133 million each year to the value of agriculture in the state.

When it comes to produce, New Jersey is among the top 10 producers nationally of several crops, including: eggplant ($6.1 million), tomatoes ($47.3 million), cranberries ($19.9 million), spinach ($4.9 million), bell peppers ($52.6 million), asparagus ($10.6 million), squash ($16.4 million), peaches ($18.9 million), cucumbers ($12.4 million), blueberries ($68.9 million) and sweet corn ($26.7 million), according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Ben Casella, a field representative at New Jersey Farm Bureau – a private, nonprofit, membership organization that represents farmers and other ag professionals, put the industry in context. “For a small state, we are still a big producer of fresh fruits and vegetables,” he said. People don’t think of us as being that large of a producer for different produce, but the reality is that the numbers show that 12% of our farms produce 80% of the production [in New Jersey].”

“In New Jersey, we have two different sectors in agriculture. We have our wholesale industry, which are selling directly to brokers and going to supermarkets. And then you have your direct marketers, which are your road stands and those type that may be selling or selling directly to the consumer, either through their own road stand or community markets, which has been a huge benefit to the growers that have been able to take advantage of that,” said Cassella.

“Our growers have had to become extremely efficient to compete [with domestic and international growers]. And that’s probably been their biggest asset because we have some of the best growers in the country because they use some of the cutting-edge technology,” Casella said.

“I think the ones who have been able to adapt are the ones willing to do innovative things to thrive and survive,” he said, adding, “The Rutgers Cooperative Extension plays a big role in providing research and expertise within the industry, so that obviously helps growers with innovation and basically research for new crops and chemicals to use.”

Growing up

Through a mix of consolidation and preservation efforts, the number of acres used for farming in New Jersey is beginning to tick up after several decades of declines due to development.

Between 2012 and 2017, farmland in New Jersey grew by 9%, bolstered mainly by an increase in farms of fewer than 100 acres, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s most recent Census of Agriculture.

When it comes to who is farming those acres, Schilling said, “There’s two groups – the first are younger people that are coming from within a farm family. Then, there’s some that are coming in as a first generation. They’re not coming in and farming a thousand acres. They’re coming in farming 15 acres, 7 acres. And it is truly staggering how much you can produce, especially in vegetables or fruits, off of an acre of land.

When it comes to produce, New Jersey is among the top 10 producers nationally of several crops, including peaches ($18.9 million production value).

“So, some of these folks are employed maybe in a full-time job off the farm, and they’re doing this because it’s a passion of theirs, and they are earning maybe not their full livelihood, but income nonetheless,” he explained.

Despite the increase in farmland and overall agricultural products sold, the average net income for farmers in New Jersey is declining, likely due to the high cost of operating in the state.

To help support farms, Atchison said the state Agriculture Department tries to make New Jersey farmers aware of the various federal grant programs, as well as those through the New Jersey Economic Development Authority, and work with them through the application process.

Still, farmers continue to be challenged by market competition, rising land and input costs, encroachment from sprawl, supply chain woes, complex regulations and weather.

“Our labor expenses are growing astronomically,” Casella said. “For the typical farm, their labor expense may be 40% of their expenses. For your produce, high hand labor type operations, it can get pretty expensive as far as the labor. So, growers are looking for ways to basically streamline, become more efficient and that’s the struggle they’re facing – trying to maintain their bottom line while competing not only globally, but even nationally.”

Schilling agreed, saying, “The highest percentage of our production expenses are labor, on average, across the industry.”

“But what’s more deceiving is that if you’re doing certain things like produce or nursery, your labor costs are even higher. So, you’re making more money, but you’re spending more money. It’s a real challenge. And then when you throw in some of these other price increases, cost increases, it’s been a challenge. And then let’s throw in a kicker — mother nature,” he said.

Schilling said, “We’re not the big Midwestern states where one of the pathways to profitability is to farm more acreage … In New Jersey, we tend to be smaller farms and we tend to be much more diversified. Not to say we don’t grow commodities like corn, wheat or hay, but a lot of our farms are producing higher value crops.”

[I[f you’re doing certain things like produce or nursery, your labor costs are even higher. So, you’re making more money, but you’re spending more money. It’s a real challenge. … And then let’s throw in a kicker — mother nature.

– Brian Schilling, Rutgers Cooperative Extension and New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station

“We’re what is often called ‘a specialty crop state.’ Think of that as vegetables, fruits, nursery products – things that are not your big commodities. So, the great thing about those crops is they tend to produce higher returns per acre, more money per acre. The challenge is they tend to be more intensive,” he said.

“One big challenge here is if you can get the labor you need, it tends to be more expensive than in other parts of the country. And if you stop and think about it for just a moment, farmers are competing oftentimes for labor with restaurants, landscaping businesses, areas where people might be able to earn a similar or higher wage in an environment indoors that might be more indoor work, for example, in a restaurant. So even though we have a high minimum wage, which is an often-cited challenge among agricultural folks, so many of our farmers have to pay more than a minimum wage just to get workers because there’s so much competition,” he explained.

Ripe for visitors

While the majority of farming in South Jersey continues to focus on wholesale operations, agritourism is taking root at farms in other parts of the state, particularly small and mid-sized farms in North Jersey that are looking for ways to add value to their products.

“With the increase of development in some areas brings customers, which brings opportunity and has made the industry a lot more economically viable because now they have a larger customer base,” Casella said. “And they’ve kind of evolved into direct marketing events because that’s what the customer is looking for.”

In addition to direct sales, farmers are tying into other potential income sources, like community markets and farmers markets, and trying their best to “successfully market themselves and stand out,” he said.

Schilling said, “If you’re farming 50 acres – which may not be big by a Midwestern farm standard – is a lot of land with a lot of productive capacity. But at the same time, you’re not going to be supplying a major retail chain, so you’re probably best advised to consider a direct marketing channel, a farm market or some other arrangement.”

“Direct marketing is definitely something that I see more and more folks looking at,” Schilling said. “But that’s also in part because we do see some of the folks coming in as small, maybe first-generation growers, and they just simply don’t have an option of going into a wholesale channel. So, I do think kind of direct marketing and agritourism is something that is trending.”

Off-farm agritourism may include setting up shop at a farmers market or local festival, while on-site activities range from direct-to-consumer sales, like community supported agriculture, u-pick and on-farm markets. Educational tourism – such as school or group tours and wine tastings, as well as entertainment (hayrides, corn mazes, petting zoos and haunted barn experiences) and recreation (horseback riding, hunting, fishing and bird watching) are also popular.

Additionally, farms are branching out more into events, like birthday parties, weddings and concerts, an offering that is being made easier thanks to the state’s recently enacted law allowing certain commercial farms on preserved farmland the ability to host special gatherings.

Under a bipartisan measure signed into law last February by Gov. Phil Murphy, farms that produce agricultural or horticultural products worth $10,000 or more annually can now seek permission from the state to host festivities, subject to certain conditions.

As part of the law, counties and municipalities that hold development rights on preserved farmland are required to develop an application process by which people can apply to host special events, review applications received and forward relevant information to the State Agricultural Development Committee.

Feeding the animals is just one of the many children’s activities offered at Alstede Farms in Morris County. – NJBIZ FILE PHOTO.

Schilling said, “From the general public perspective, agritourism is just a wonderful thing. It’s a great time to enjoy the fall season or kick it off in the spring, whether it’s a pick-your-own, a haunted hayride or cutting down your Christmas tree at a farm that you used to do it at with your parents or grandparents, there’s so many great traditions.”

“But another thing about agritourism is if you stop and think about it, you’re really gambling as a farmer. You put seed and fertilizer and labor into the ground. You watch the crop grow, you hope that it grows well and yields well. And then you harvest it, and you get income at the harvest – which may be late in the year,” he said.

Agritourism enables a farmer to earn income at different times of the year and have more of a steady stream of revenue, Schilling said.

“That’s a great diversification mechanism. And, you’re not getting a wholesale cost, you’re getting the full retail cost when you direct market your product,” he said. “It is a different business model, so you need labor, infrastructure and insurance and you still have to spend money to make money, but some direct marketers can do very well in this environment.”

Schilling noted that there are some farms – such as Alstede Farms in Morris County – that are doing a combination of wholesale, as well as offering retail through an on-site farm market and providing experiences, such as pumpkin picking.

Wined up

In order to tap into the direct market and ability to sell directly to the consumer, some of the state’s fruit growers have transitioned into wineries, which has now become the fastest-growing segment of agriculture in New Jersey, generating close to $4.69 billion in total economic activity, including more than $92 million in annual tourism expenditures.

According to the Garden State Wine Growers Association, New Jersey is one of the top producers of wine in the U.S. Statewide, its vineyards grow more than 80 grape varieties, including Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Pinot Noir, Riesling, Sangiovese, Albarino and Chardonnay, while the state’s 50-plus licensed wineries also produce a wide array of fruit wines.

Casella said, “There’s a lot of smart people in the wine industry and they’ve been successful in marketing their product. We have some pretty good wineries that are creating a name for themselves, but then also doing a good job of promoting, getting involved with tourism and doing the promotions to let people know that they’re there.”

The Garden State Wine Growers Association kicked off the 2022 New Jersey Wine Week with a reception at Drumthwacket, the governor’s mansion, to recognize the 2022 Governor’s Cup winners. From left: Charlie Tomasello and Brian Tomasello, of Tomasello Winery; First Lady Tammy Murphy; Gov. Phil Murphy; Jack Tomasello of Tomasello Winery; and Louis Caracciolo, Amalthea Cellars, president and marketing chair of the Garden State Wine Growers Association. – JESSICA HENDRIX PHOTOGRAPHY.

“I think that’s what the public is looking for, getting out to an open space, getting out to a farm, a different type of slower paced night out, going to a winery for a wine tasting or some type of event,” he explained. “And that’s kind of where I think some of the agricultural side has went, too, with farm to table, having different events where they may have a chef come out and prepare the food for a special dinner type tasting and stuff like that.”

“I think just getting the public out to the farms has been a good endeavor by a lot of our growers, what they’re looking for. It just seems to be that’s been a very good opportunity that growers have been able to take advantage of and people seem to enjoy,” he said.

“The thing about a farmer is that they have to be an entrepreneur, and if they’re not entrepreneurial, they’re going to get left behind,” said Newell Thompson, executive director the New Jersey Agricultural Society, which works to preserve and enhance farming around the state. Founded 242 years ago, it is the nation’s oldest such organization.

“There’s a lot of pressure on the farmland to be converted into warehousing, solar fields, real estate development. And so, the farmer who is already struggling to make money sees this kind of low hanging fruit money from let’s say a warehouse company. And that really kind of disrupts succession planning or causes the farmer to abandon ship,” Thompson said.

To help create an economy that is sustainable – both environmentally and financially –Thompson believes stakeholders need to agree on a common vision.

“We are woefully behind in how we address agriculture from an infrastructure standpoint. And again, that’s not only at the governmental level, but it’s also the trucking industry, the processing industry, the whole supply chain really needs to be carefully looked at and addressed as if you are going to be a farmer and can you be successful in New Jersey,” he said.

“We’re the Garden State because we can grow a diverse array of products and we have a population that has the appetite and the capacity to buy those products,” Thompson added. “And our vision and our mission in New Jersey should be to look at where we are and then look at the current conditions with climate, our water resources and our geopolitical issues and produce local food communities that are going to nourish and enhance people’s lives in New Jersey.”