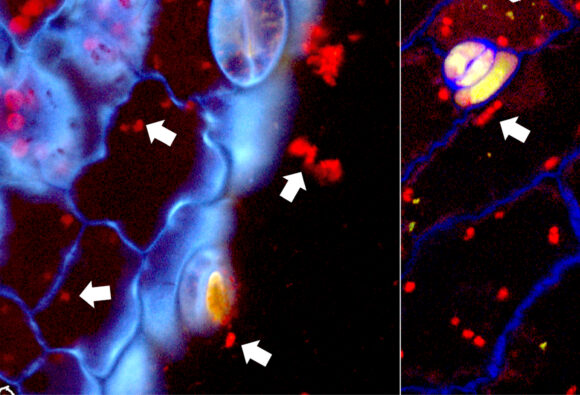

Confocal microscope images of clover leaves showing red-stained bacteria (arrows) within leaf cells. James F. White and Qiuwei Zhang/Rutgers University-New Brunswick.

Rutgers researchers have discovered that nitrogen-fixing bacteria hidden within leaf cells could lead to more efficient and sustainable methods of crop cultivation.

The study, recently published in the journal Biology, investigated how bacteria in non-photosynthetic leaf cells of seed plants can naturally provide nitrogen to plants. Currently, inorganic nitrogen fertilizers, such as ammonia or nitrate, are commonly applied to soils, damaging soils, and causing nitrogen runoff that contaminates streams, rivers, and other water bodies.

Prof. James White.

“Development of new crop varieties or agricultural technologies based on rebuilding and supporting native nitrogen-fixing endosymbiosis could dramatically change how we cultivate crops,” said James White, a principal investigator of the study and professor of plant biology at the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences (SEBS) at Rutgers University-New Brunswick. “This discovery will pay dividends in preservation of the environment, regeneration of agricultural soils and reduction of global warming by cutting the release of greenhouse gasses and environmental degradation that results from fertilizer runoff.”

Prior to this study, it was commonly understood that nitrogen-fixing symbioses were limited to roots of legumes and a few other families of plants that form root nodules containing nitrogen-fixing bacteria. But by examining more than 30 species of seed plants in 18 families of monocots and dicots, the study investigators found that bacteria in leaf cells can exchange nitrogen for plant sugars.

This discovery shows how non-domesticated plants, such as wild or weed plants, grow in non-fertile soils without the addition of nitrogen fertilizers. Instead, plants harvest nitrogen from the air using intracellular bacteria that they absorb into their cells from soils and carry in seeds.

The most efficient of these cryptic nitrogen-transfer endosymbiosis was seen in the glandular trichomes (also known as leaf hairs) of dicot plants like hops (Humulus lupulus) and hemp (Cannabis sativa). Glandular trichomes contain terpenoids, cannabinoids, essential oils or other antioxidants that may increase efficiency of endosymbiotic nitrogen fixation by scavenging or excluding oxygen that inhibits nitrogen fixation.

White said expanding our knowledge of how plants extract nitrogen from endosymbiotic bacteria within leaves could help growers find more efficient and sustainable ways to fertilize crops.

“This research shows that it may be possible to support nitrogen-fixing activities by endosymbiotic bacteria in leaves by breeding plants to preserve native endosymbiosis or by applications of microbes to plant seedlings to re-establish nitrogen-fixation endosymbiosis,” he said. “Our hope is that this study will open doors to the development of new methods of crop cultivation that are more efficient and sustainable than what is currently practiced.”

In addition to Rutgers researchers, the study involved collaborators at the U.S. Geological Survey, University of the Sacred Heart in Puerto Rico and University of the Valley in Colombia.

This article first appeared in Rutgers Today.