Zoe Orlino installing bricolage objects representing the marsh plants’ growth cycles.

In March 2021, Zoe Orlino, a graduate student in the Department of Landscape Architecture at Rutgers, installed a series of bricolage art pieces at the Abbott Farm Marshlands in Hamilton Township, New Jersey. As the culmination of her thesis research on design, making and representation, these handcrafted pieces reveal the hidden story embedded in the marsh’s landscape.

The genesis of the project can be traced back to 2019 when Orlino took a praxis studio in the Department of Landscape Architecture led by associate professor Kathleen John-Alder. The studio focused on designing an ecologically driven amusement park at Spring Lake, an area within the Abbott Farm Marshlands, which, from 1907 to 1920, was home to the White City Amusement Park. Today, Spring Lake is a protected wetland preserve and part of the John A. Roebling Park. Remnants of the amusement park, like a grand staircase that took visitors into the park, remain within the area as a testament to history. Throughout the studio, Orlino and her colleagues heavily studied and mapped the park’s existing conditions and site analysis in order to create several design proposals. She was captivated by the sights and sounds of the marsh, and subsequently selected it as the site of her master’s research project.

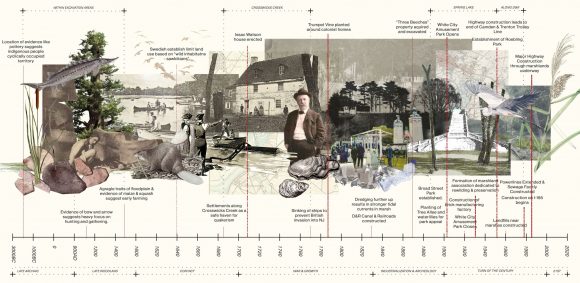

Zoe Orlino’s timeline map of Abbott Farm Marshlands.

Orlino’s master’s thesis expands the historical analysis completed during the studio and documents this research with an illustrative timeline that details natural and anthropogenic change. She then used this information as the basis of an art installation comprised of objet trouvés and bricolage. An objet trouvé is an object found by chance, treasured for its aesthetic value and subsequently re-presented as art. These salvaged objects can include naturally formed or man-made artifacts. Bricolage is an artistic process of construction using whatever material is readily at hand, which in this particular instance were the found objects – the objet trouvés – that Orlino collected during her visits to the marsh. When she finished the assemblage of the bricolage pieces, she returned them to the marsh.

Zoe Orlino’s first bricolage piece, a weaving composed of objet trouvés, which she placed at the top of the grand staircase of the former amusement park.

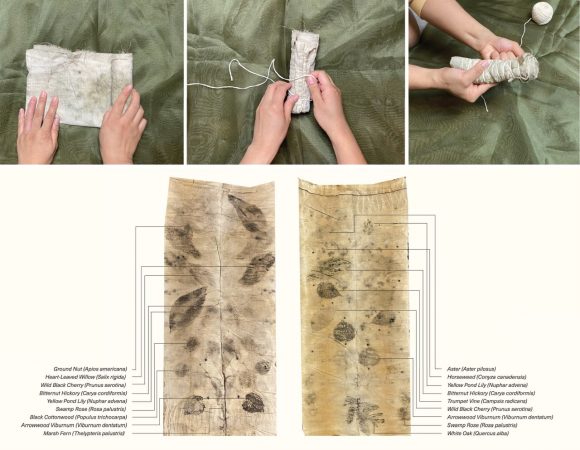

She placed the first bricolage piece, a weaving composed of objet trouvés, at the top of the grand staircase of the former amusement park in order to ask visitors to contemplate the stairs’ purpose and placement within the marsh. Another bricolage, a circular interpretation of Spring Lake inspired by a mapping exercise conducted during the praxis studio, depicts the lake as a “void” surrounded by a rich palette of plants. By framing the nearby power lines in the distance, this piece also asks viewers to contemplate the relationship of the marsh to progress and anthropogenic change. The final bricolage, an eco-print, uses the natural dyes found in the plants the indigenous people of the marsh, the Lenni Lenape, would have utilized. The completion of this piece required rainfall, and nature’s participation, to release the plant dye that covered the fabric.

According to Orlino, the discovery of the objet trouvés, the assemblage of the bricolage and the installation of these pieces in the marsh, following ideas expressed by Robin Wall Kimmerer in Braiding Sweetgrass, became a form of gift giving. Nature gives the objet trouvés, the artist gives the bricolage and the installation forges a connection among the individual, community and nature. This notion of gift economics is what Orlino believes reveals one’s deeper connection with the marsh.

Zoe Orlino’s final bricolage is a demonstration of eco-print technique that uses the natural dyes found in the plants.

Mary Leck, a botanist who has studied the marsh and its plants for many decades noted, “Zoe’s pieces made me consider how transient art pieces might fit into a natural landscape – they enhanced my vision of a landscape I’ve known for many years. This tidal freshwater wetland has long been a source of inspiration to me as I’ve studied seed germination ecology and documented the diversity of plants that grow there. It’s great fun to have someone like Zoe show me another way of seeing!”

Patricia Coleman, president of the Friends for the Abbott Marsh, who like Leck worked with Orlino during her thesis research, said, “It was a great pleasure to see the evolution of Zoe Orlino’s project in the Abbott Marshlands. Her artistic talents are stunningly impressive. What I found most surprising was her sense of reciprocity with the landscape. She was quick to recognize found ’treasures’ and willing to create and share her own artistic treasures in return. Her generosity of spirit was both wonderful and inspiring to witness.”

A week after the installation, when Orlino returned to the marsh to check on the woven bricolage placed at the top of the stairs, she passed a fisherman who saw her take pictures of the piece and asked if she knew “why they put that there.” He then explained that he had seen the other bricolage pieces throughout the marsh on his walks around Spring Lake, and they had prompted him to search for more. Elated, she asked what he thought of the pieces. The fisherman paused and then stated, “It felt like they were always there.”

The pieces featured throughout the outdoor exhibit were guided of her thesis committee, which was comprised of Kathleen John-Alder, Holly Nelson, associate professor of professional practice, and Arianna Lindberg, instructor in the Department of Landscape Architecture, as well as Mary Leck and Pat Coleman, experts of the Abbott Farm Marshlands.