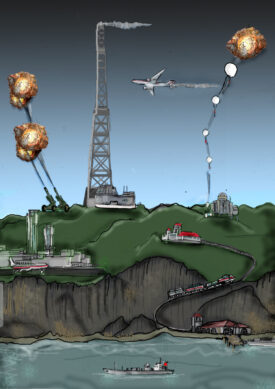

Potential geoengineering methods for injecting sulfur dioxide into the upper atmosphere to create sulfuric acid clouds that limit global warming. Image: AGU/Brian West

The technology’s regional impacts depend on how much greenhouse gas emissions are reduced

Could we create massive sulfuric acid clouds that limit global warming and help meet the 2015 Paris international climate goals, while reducing unintended impacts?

Yes, in theory, according to a Rutgers co-authored study in the journal Earth System Dynamics. Spraying sulfur dioxide into the upper atmosphere at different locations, to form sulfuric acid clouds that block some solar radiation, could be adjusted every year to keep global warming at levels set in the Paris goals. Such technology is known as geoengineering or climate intervention.

But the regional impacts of geoengineering, including on precipitation and the Antarctic ozone layer hole, depend on how much greenhouse gas emissions from humanity are being reduced simultaneously. If carbon dioxide emissions from burning coal, oil and natural gas continue unabated, geoengineering would not prevent large decreases in precipitation and depletion of the life-sustaining ozone layer. If society launches massive efforts to reduce carbon emissions, remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and adapt to climate change, small doses of geoengineering may help reduce the most dangerous aspects of global warming, the study says.

“Our research shows that no single technology to combat climate change will fully address the growing crisis, and we need to stop burning fossil fuels and aggressively harness wind and solar energy to power society ASAP,” said co-author Alan Robock, a Distinguished Professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences in the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences at Rutgers University–New Brunswick. “This mitigation is needed whether society ever decides to deploy geoengineering or not.”

Using a climate model, scientists studied whether it’s possible to create sulfuric acid clouds in the stratosphere to reflect solar radiation and limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) or 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial temperatures. Those two goals were set at the 2015 United Nations climate change conference in Paris to try to reduce the negative impacts of global warming.

Robock noted that the study was done with only one climate model that addressed different global warming and geoengineering scenarios. Other studies are needed to check the robustness of the results and to further examine the potential risks of any geoengineering scheme.

Lili Xia, a Rutgers research scientist, co-authored study. Scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, Cornell University, University of Colorado, Boulder, Utrecht University, Delft University of Technology, University of Texas, Rio Grande Valley, Indiana University and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory contributed.

This article originally appeared on Rutgers Today.