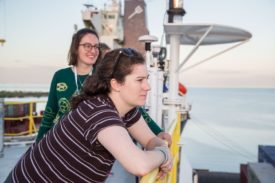

Laura Haynes cruises the world searching for core samples

By Craig Winston

It’s hard to pinpoint where you might find Laura Haynes, an EOAS post-doctoral fellow, for an interview. During a telephone chat she sounded far away. She explained why in a subsequent email.

“I was actually in Fiji, eating breakfast before we headed out to board the ship,” she wrote. “We are now transiting nine days to our first coring site and will be drilling to about 670 meters below the sea floor in the hopes of recovering the K/Pg boundary.”

Translation: The Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary marks the mass extinction of the Earth’s dinosaurs more than 60 million years ago. It’s represented by a thin band of rock.

Haynes, a paleoceanographer, is sailing on the month–long International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 378 with a collective of scientists from countries including Australia, China, Japan, Korea, and Brazil. They staff a floating lab, covering it 24/7 on rotating 12-hour shifts. (The ship travels the world, drilling at five to eight locations on a cruise; this time there is only one stop for a long core drill.) The crew hopes that drilling into this new, unbroken core will enable them to reconstruct climate change in one location millions of years ago, revealing the answers to questions about the Earth’s climate history.

“It was records from ocean drilling that first showed that the ocean floor is spreading apart and causing the movement of tectonic plates, and that rapid climate change has happened in Earth’s past,” said Haynes. “While there are records of Earth history from many crucial time periods that exist on land, they are patchy and not always continuous. By contrast, sea floor muds can build up continuously and slowly over time and give us continuous records of Earth’s climate history.”

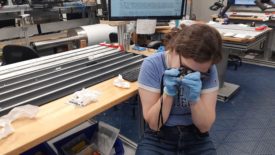

Back in the lab, the scientists examine core samples from the drilling and meet twice a day to discuss their findings. Haynes’ role on the ship is as a sedimentologist; she describes the core samples that come up from the sea floor and determines their composition: fossil, clay, sand, or volcanic ash. The expedition continues long after each member returns home with samples they take back for further study. Their scientific community will stay intact as they synthesize their findings over the next few years.

Her itinerary during the last year is an enviable one. Haynes earlier sailed on the Chilean drilling ship on a cruise to the Chile margin led by the Rutgers postdoc researcher Samantha Bova and EOAS faculty member Yair Rosenthal, both of the Department of Marine and Coast Sciences. They sought to understand how Patagonian glaciers and the South Pacific Ocean responded to climate change. “It was a huge success and a wonderful first experience on a drillship,” she said. “I am coming to understand that I was spoiled by the incredible wildlife we saw on the ship; we were encircled by albatrosses and seals for most of our expedition.”

Her primary field of study involves using fossilized shells of plankton, “foraminifera,” to reconstruct the history of climate change. The shells are preserved in deep sea muds, and their chemical composition can indicate past climate such as ocean temperature, acidity, and circulation. “These are all things we’d like to understand so that we can better predict how modern climate change will affect the Earth system in the future.”

Haynes was inspired to pursue a career in the sciences when she had an awakening in high school after watching “An Inconvenient Truth,” former Vice President Al Gore’s 2006 documentary intended to educate the public about global warming. After that, she intuitively understood that she wanted to dedicate her career to studying the environment.

Haynes said: “When I got to undergrad, I was incredibly lucky in that my freshman adviser suggested I take a geology class. After going on my first few field trips, I knew that this was the field I wanted to be in, but I also knew that I wanted to apply it to understanding modern environmental change. With the study of past climate histories, I found this perfect balance.”

Her educational background prepared her well for her research career. Haynes earned her undergraduate degree in geology from Pomona College (Claremont, Calif.), and a master’s degree and Ph.D. in Earth and Environmental Sciences from Columbia University. For her doctoral dissertation, she analyzed living foraminifera, spending two months in coastal field stations at Catalina Island, Calif., and Isla Magueyes, Puerto Rico.

Perhaps a telltale sign of Haynes’ future came from her first job at age 14— as a counselor at a science camp for elementary students.

“I didn’t have any idea then that I would be a scientist, but it does make a lot of sense in retrospect. “

During her latest cruise, Haynes answered several questions about her work and life. A condensed version of her comments appears below:

What was your best day on the job?

In the lab, I always love a day when I get new data off the machine, knowing that I am the only person in the world that has this tiny new piece of knowledge.

What are your career goals?

I am incredibly excited that I will start an assistant professor position at Vassar College this fall. In my new position, I am thrilled to usher undergraduates through the research process, to conduct research on our new sediment cores, and to teach interdisciplinary classes related to oceanography, biogeochemistry, mass extinctions, and science communication.

What’s your secret skill?

I am very good at manipulating dust-sized microfossils with the smallest possible paintbrush. Working in paleoceanography has certainly honed my fine motor skills.

Which professional accomplishment has given you the most pride?

I got to mentor an undergraduate student, Ingrid Izaguirre, through a summer Research Experiences for Undergraduates project in 2018 at Columbia. She did a fantastic job and presented her findings at the American Geophysical Union conference that winter, explaining complicated ocean chemistry to interested listeners for four hours straight. I was incredibly proud of her work and presentation, and still get to see her progress as she is now a graduate student in paleoceanography.

Editor’s Note: this article originally appeared on the Institute of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences website.