Prostrate knotweed in a parking lot on the George H. Cook campus at Rutgers. Photo by Lena Struwe

Amy Gage, Ameen Lotfi, and Lena Struwe contributed to this article.

On the first warm and sunny spring Saturday this year, scientists, students, naturalists and herbaria enthusiasts alike gathered away from the sun in a Rutgers conference room for the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis: “Plants in the City” symposium on March 30. They set aside any weekend hiking or picnicking plans to discuss the future of research as we know it. Through funding by NSF, the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis project has begun a vast effort to digitize nearly one million herbarium specimens from over a dozen institutions in the urban corridor from New York City to Washington, D.C. This treasure trove of data includes specimens collected as long as 200 years ago and is now available to anyone with an internet connection and an inquisitive mind.

A pre-symposium student poster session took place on March 29 in Foran Hall.

For those not fortunate enough to have experienced one first hand, an herbarium (plural: herbaria) is a collection of preserved plant specimens and associated data used for scientific study–like a plant library or museum. Tucked away in the basement of the Biological Sciences building on Douglass Campus is one such plant specimen library–the Chrysler Herbarium. There, an army of herbarium workers and volunteers have been unpacking old plant collections and carefully digitizing them to increase access to these data. The talks at the symposium were led by scientists and herbaria curators who have already begun answering scientific questions using herbarium-derived data.

In her talk on “Herbivory through the ages,” Emily Meineke from Harvard University Herbaria coined the phrase “Herbaria as lenses into the past” and described how she used herbarium specimens to fill in spatial and temporal gaps in plant herbivory interactions. She also highlighted the opportunity for creative thinking in experimental design as researchers tackle the novel challenges of utilizing digitized herbarium data. Historical data preserved in herbaria can show how urbanization is changing the natural world. She stated, “There is specimens-collection bias near herbaria and roads…Using historical US census data, we can actually attach a metric of urban density as a way to study change in ecological processes in cities over time.”

Mason Heberling from Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Natural History is also interested in the human-driven changes that are occurring in our natural world. In his talk on “Quantifying functional trait changes through a century of plant invasion,” Heberling describes human-derived plant invasions, “We are reshuffling floras. In the forest, you look up and you see the flora of eastern north America, but you look down and you see the flora of Europe and Asia.” Heberling is using herbarium data to better understand these biological invasions in a historical context.

Myla Aronson discussed the effect of urbanization on the flora of the New York metropolitan area.

Myla Aronson from Rutgers’ Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Natural Resources used herbarium data to challenge a previously untested paradigm of urban areas–that they contain a homogenized assemblage of urban species. She found this to not always be true. “We actually find more diverse plant assemblages in the city. We cannot say as a whole that cities are a homogenizing force. Instead, we likely will see homogenization between habitat types. A vacant lot in New Jersey may have similar flora to a vacant lot in Germany, but overall cities are not homogenized.”

Matt Von Konrat from Chicago’s Field Museum elicits the help of citizen scientists to use digitized herbarium specimens to tackle somewhat technical or even esoteric questions about liverwort plants. Even though they are not liverwort specialists, these citizen scientists are able to gather quality data. He shared, “Some scientists may think you’re never going to get the general public to be able to do this work.” Konrat stated that 12,000 people made over 100,000 measurements on digital photos of liverworts for this research. He is passionate about the democratization of science and sees these digital herbaria as a staircase to increase accessibility to the ivory tower. He states, “To train the next generation of scientists and increase access to science, these tools are incredibly powerful.”

Black locust: collected by Franklin Parker in 1879, on the banks of the Delaware River in Camden. This specimen was donated to Rutgers from Princeton University, as can be seen on the stamps with accession numbers. The barcode is a unique visual ID for the digitizing. © Rutgers University

Von Konrat’s vision for the next generation is evident via the involvement of current and former Rutgers students in the symposium and data digitization. Megan King, graduate of Rutgers School of Environmental and Biological Sciences (SEBS), is the collections manager at Chrysler Herbarium. King spoke at the symposium on how the undergraduate “Herbarium Army” is the force behind the success in getting herbarium specimen data into online global portals at Rutgers. SEBS undergraduate student Ameen Lofti led the Landscape Change Analysis workshop with Myla Aronson, demonstrating how to use ArcGIS for analyzing land use trends in the Mid-Atlantic region. Lotfi commented, “Understanding the influence of land use on floras is important for conserving and restoring nature in cities.”

Rutgers professor and Chrysler Herbarium director Lena Struwe noted the significance of digitizing this historic information, “Millions of plants have been pressed and saved in scientific museums and herbaria over the last centuries and fueled the discovery of new species, understanding of plant evolution and conservation efforts. However, until the last decade or so, to investigate these collections and use them in research, scientists would have to physically visit each herbarium to see the actual collections or have large amounts of specimens sent to them on loan. With the new technology of large scale databasing and digital photography of museum specimens (digitization) we have now opened the museum collections hidden inside steel cabinets for the world to see. Instead of bringing the scientists to the specimens we are now bringing the specimens to the scientists on their computers.” She notes, “Of course, physical specimens are still needed for anatomical, chemical and DNA studies, but a lot of interesting and urgent research can be done with digital herbarium specimen data. That is what this symposium was about, and national keynote speakers were invited to share their research results and methods to inspire the audience.”

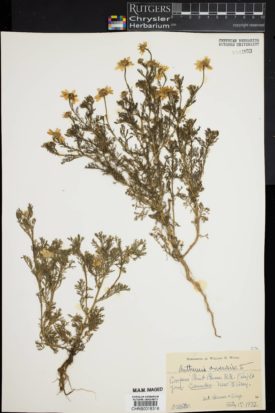

This specimen of a corn chamomile, a weedy species related to daisies and chamomile, was also found in Camden, along the Pennsylvania Railroad’s freight yard. It was collected by William H. Witte in 1935, when steam trains still ran along the Delaware River. © Rutgers University

The workshops at the symposium guided the audience on how to put these ideas and resources into practice–how to: analyze land use and climate changes using herbarium specimens; engage students in seeing landscapes and plants and avoid plant blindness; create a campus flora using digital observation tools; and to track changing flowering times due to climate change. “The possibilities are many, customizable, and addresses urgent research needs in today’s world,” said Struwe.

Struwe captured the magnitude of this chapter in research, “What we are witnessing is a second revolution in plant systematics and herbarium-based research. The first one was the introduction of molecular methods to understand the evolution of plants starting in the late 1990s. What we see now is another technology that is revolutionizing and introducing new data to this research field, the digitized scientific collection data. Each collection is a snapshot in time and place, a proof of what was where and when.” Struwe continues, “By taking these snapshots, knowing their species identity and locality and age, and accumulate many thousands and more of them, we can then build models of the past, current and future. What will the vegetation look like in the future? When will plants flower and fruit? How will pollinators and other animal species be affected? A lot of the clues to these answers are no longer hidden inside closed museum cabinets.”

Online access to the Mid-Atlantic Herbaria Consortium specimens collections