Courtesy of Department of Animal Sciences

At the dawn of Rutgers Cooperative Extension in the early 1900s, New Jersey farmers were facing an era that offered promise of new methods of farming that would solve problems, improve efficiency and bring a better return on their dollar. Extension specialists and agricultural agents implemented a variety of methods and practices to engage farmers. One such example, which took root in New Jersey and went into the annals of agricultural history in the U.S., is the development of artificial insemination in dairy cows.

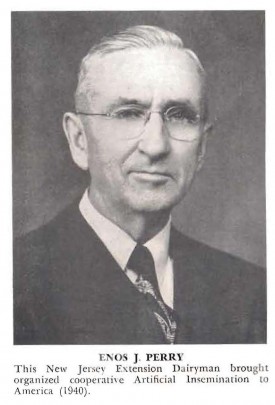

Enos J. Perry (1891-1983) served Rutgers University from 1923 to 1956 as an extension specialist in dairy husbandry. His greatest contribution to agriculture was the establishment of the first cooperative artificial breeding association for cattle in New Jersey and the U.S. and the practical application of the technique of artificial insemination (AI) of farm animals. Perry initiated the first dairy cattle AI Co-op in the U.S. in 1938, and his book “The Artificial Insemination of Farm Animals,” published in 1945, was the standard reference manual on the subject, providing vital information on artificial insemination for thousands of workers and students.

Calvin G. Wettstein was the Hunterdon County agricultural agent for Rutgers Cooperative Extension from 1966 – 1987. He did his graduate research at the Dairy Research Farm in the early 1960s. Now retired, Wettstein described the start of Perry’s work in AI. “Dwight Babbitt was Hunterdon County agriculture agent from 1934-1959. He was an effective agent, and an interesting person. In 1937, he brought extension specialist, Enos Perry, to a Hunterdon County Board of Agriculture meeting. Enos Perry had just returned from a trip to Europe, including Denmark, where he had observed a cooperative formed to provide breeding services by artificial insemination of dairy cattle. Perry presented the information he had collected in Denmark to the Board. The Board of Ag responded with an effort to develop an AI cooperative. With considerable effort by the Board and that of Dwight A. Babbitt and Enos J. Perry, the first farmers’ cooperative was formed, “The Cooperative Artificial Breeding Association, Unit #1.” This made it possible for small farmers to, first and foremost, eliminate the use of a bull, a very dangerous animal on the farm, and to improve the genetic makeup, milk production and physical conformation, using top flight, proven dairy bulls.”

John W. Bartlett c. 1930.

Courtesy of Department of Animal Sciences

In addition to Hunterdon County dairymen, the project attracted the support of the New Jersey Holstein Association. John W. Bartlett, chair of the Rutgers Department of Dairy Science, also supported the idea and plans were set to include dairymen in Somerset and Warren counties, with the county agents assuming a leading role. The groundbreaking organizational meeting was held on March 28, 1938, in the historic Hunterdon County Courthouse in Flemington.

With Perry’s assistance, the managing committee recruited Falmer Larsen from Denmark for six months to be the demonstrator and advisor in the beginning. Perry also arranged for J.A. Henderson, DVM, then working on his master’s degree at Cornell Veterinary College, to work for a year as the inseminator.

According to the publication Pennsylvania and New Jersey AI Cooperatives: The First Forty Years by William Schaefer, “Forty five dairymen from the three counties paid an enrollment fee of $5.00 and elected a ‘managing committee’ with Clifford E. Snyder of Pittstown as chairman. The first bulls used in the cooperative breeding program in New Jersey were housed at the Peter Van Nuys Farm in Belle Mead.” Schaefer continues, “May 16, 1938, was “D Day” for AI in this country. After suitable opening day ceremonies at the Van Nuys farm, Doctors Henderson and Larsen, accompanied by County Agent Dwight Babbitt, took off to ply their new trade as they inseminated cows on four farms in the newly organized three-county area. This began a trend that would eventually isolate the bulls from the cows so completely that future generations would probably never observe a natural mating at a dairy farm. The day of leading “old Bessie” down the road to mate with a neighbor’s bull was at an end.”

Schaefer summarized the significance of that day. “The dairymen who entrusted their cows to artificial insemination, using semen from a test tube, were truly pioneers, and they were the first to use cooperative artificial breeding in this country. Therefore they deserve to be listed for posterity. Dr. Henderson inseminated cows that day for Fred Mayer in Somerset County, Kingman Brothers at Three Bridges, and Clifford Snyder at Pittstown in Hunterdon County, and for Hans Schanzlin at Montana in Warren County. The first page of AI history in the United States was recorded.”

The first calf born via artificial insemination in the U.S. in February, 1939 was at the Schomp Farm in Stanton, NJ. At the time it was considered the most photographed and publicized bovine in history. Courtesy of Rutgers Department of Animal Sciences

Although some farmers were quick to become a part of the development of this new method, others were hesitant. In the Summary of Oral Interviews Created as Part of an Artificial Insemination Documentation Project, stored in the Archives of Cornell University’s Kroch Library, summary author Robert H. Foote states, “The extension service had a big job to do in educating dairymen of what AI could do. Many farmers would like to have access collectively to popular bulls that were restricted to the better known cattle breeders.” From Perry’s oral interview, Foote summarizes, “New Jersey farmers now wanted access to a Rutgers Holstein bull siring daughters testing close to 4% butterfat. Dr. Bartlett gave his O.K. for this, although he was concerned that AI would not work. A failure would reflect unfavorably upon the college.”

There was no need for worry, though. “The first calf born was normal, as were others. It was a highly photographed calf. Some still laughed at AI because in one herd the first nine calves were all bull calves. However, “he who laughs last, laughs best,” as the next 10 calves were all heifer calves.”

New Jersey was the birthplace of AI in the U.S., initiated by the development of small AI coops in 1938, followed by New York two months later. The practice of artificial insemination spread as cooperatives were formed across the country.

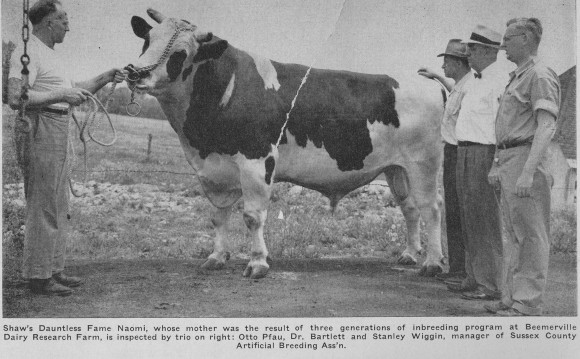

A chain around the horns and through the nose ring was the method used to control dangerous dairy bulls. Pictured on the right are John Bartlett (center) and Stanley Wiggin (far right), Sussex County AI manager. Courtesy of Rutgers Department of Animal Sciences

With this innovation in breeding available to U.S. farmers, they now had access to a means to improve the quantity and quality of their product. AI allowed for selective breeding so that traits like high milk yield, high butterfat and good body proportions were bred into their herd. And, as surprising as it may seem, AI saved lives. When Wettstein and his wife, Elizabeth were newlyweds, they lived on the Dairy Research Farm, a part of the Agricultural Experiment Station in northern New Jersey. Citing incidents of people getting gored by bulls, Elizabeth recalls “They were dangerous. There were many injuries and deaths.”

The groundbreaking nature of the introduction of artificial insemination in New Jersey and the work of Enos Perry is not lost on Schaefer. “Certainly the New Jersey cooperatives wrestled with the difficulties of “being first” as they entered the artificial breeding field before any other state, against unknown and uncertain odds. The generous support and leadership of Professor Perry and others who had faith enough to lay the groundwork and try a new and questionable venture, definitely branded them as pioneers.”

What role does AI play today? Currently 80 percent of all dairy cows in the U.S. are bred by AI and selective breeding through AI has contributed to improvements in the dairy industry. New Jersey AI cooperatives have disappeared along with the state’s dairy farms. Mike Westendorf, extension specialist in livestock and dairy, who conducts the current dairy cattle artificial insemination course at Rutgers, reflects on this transformation. “Times change. At one time New Jersey had nearly 6,000 dairy farms; now less than 75. In 1945, the U.S. had 2.4 million dairy farms; today less than 50,000. At the same time, herd size has gone from less than 15 cows per farm to nearly 200. And production has increased from less than 5,000 pounds per cow, per year, to over 20,000 pounds. This trend has shown no sign of leveling off.”

Perry Residence Hall on the George H. Cook Campus

For his revolutionary work in cattle breeding, Enos J. Perry was inducted into the National Agricultural Hall of Fame in 1984. One of 39 members, and two inductees from New Jersey, Perry was honored for his “outstanding national or international contribution to the establishment, development, advancement, or improvement of agriculture”.

Rutgers has paid tribute to Perry in the naming of a residence hall, Perry Hall, and a library in the the animal science building, Bartlett Hall, both on the university’s George H. Cook Campus in New Brunswick. In June of 2014, Margie Perry Gruber, daughter of Enos Perry visited the campus and generously donated some memorabilia of her father’s, which is on display in the Perry Library in Bartlett Hall.