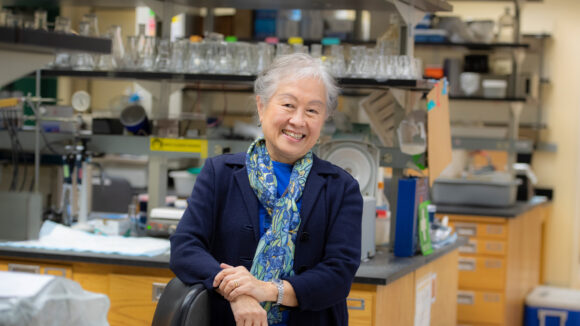

Lily Young, Distinguished Professor, Department of Environmental Sciences, is among 106 new members of the National Academy of Engineering within the United States and 18 internationally. Photo: Nick Romanenko/Rutgers University.

Lily Young has conducted research as an environmental microbiologist at Rutgers for more than 30 years

Lily Young has spent more than three decades at Rutgers using her skills as a scientist to gain a better understanding of the contaminants in the environment while working with engineers to find a solution to fix the problem.

“I became an environmental microbiologist because one of my professors in graduate school convinced me that microbes are the best chemists in the world, and that they carry out chemistry for their own benefit, which we can adapt for ours,” said Young, Distinguished Professor in the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences (SEBS). “Then working with engineers, I quickly learned that they ask different questions and are problem solvers.”

Young was recently elected to the National Academy of Engineering (NAE), among the highest professional distinctions bestowed to an engineer. She was among 106 new members within the United States and 18 internationally who were recognized for making outstanding contributions to engineering research, practice and education and for significant contributions to the field of technology, traditional engineering and innovative approaches to engineering education.

Her research focuses on anaerobic microbes – organisms that can survive and grow in an environment where there is no oxygen and degrade harmful compounds in gasoline and petroleum. These microorganisms have evolved and flourished, and scientists are determining their unique processes and environmental benefits, including curbing climate change.

“Professor Young is very deserving of this recognition by the National Academy of Engineering. Her groundbreaking research over decades revealed what types of bacteria are involved, how they do this and how their activity could be enhanced and monitored in the environment,” said Donna Fennell, professor and chair in the Department of Environmental Sciences at SEBS. “Since environmental contamination with petroleum products is so common, and since many contaminated environments such as groundwater or sediments lack oxygen, her work directly led to methods to clean up oil and gasoline pollution.”

Most of Young’s work has been done through studies in the East River in New York City, the Arthur Kill in New York and New Jersey and other areas with high contamination and where billions of pounds of pollution are released into waterways. Her findings have opened a new approach to environmental restoration and a greater understanding of the novel biochemical mechanisms of these microbes.

“This work has given us new insight into how microbes in the environment have evolved ways to transform a wide group of contaminants into harmless by-products by using them as a carbon (food) source,” Young said. “This has been valuable to civil and environmental engineers who have used this knowledge to develop environmental cleanup practices.”

Her work in environmental microbiology began 50 years ago at Harvard University, where she earned her doctoral degree in environmental microbiology; she went on to work as an assistant professor at Stanford University in the environmental engineering program in the department of civil engineering.

The engineers Young worked with early in her career looked at problems differently than research scientists, which gave her the ability to look at outcomes more holistically, she said.

“I learned to look at what went in at the beginning and what came out at the end,” she said. “You might not know exactly why or how something happened, but you knew that it did and that is the start of your investigations.”

When Young arrived at Rutgers in 1992 from NYU Medical Center, she came at the urging of a professor in the chemical and biochemical engineering department. At the time, Young and her team were investigating the molecular biodegradation of toluene, a component of gasoline. It was when gasoline contamination from old, leaking underground storage tanks was widespread. The research revealed how certain strains of bacteria found in the environment could metabolize and remove toluene in conditions where there was no oxygen.

“Using naturally occurring microbes to biodegrade gasoline and other compounds has been validated and has evolved into an accepted and environmentally friendly method for cleanup by environmental engineers,” said Young who, with others from Rutgers, began her career at the university by securing a $5 million, six-year federal grant to examine mixtures of petroleum wastes underground.

Besides her work at SEBS, Young has held a variety of positions, including associate dean for graduate studies at SEBS, the chair of the Department of Environmental Sciences, dean of international programs at SEBS and the provost for faculty development and excellence at Rutgers-New Brunswick.

“I’ve learned a lot here at Rutgers, and it is rewarding to see that many students continue to have strong interest and dedication in promoting and preserving our environment,” Young said.

This article originally appeared in Rutgers Today.