Distinguished Professor Debashish Bhattacharya‘s four-year collaborative research project on the coral heat stress phenome is sponsored by the National Science Foundation with a $509,125 grant. His project will use genomics, genetics, and cell biology to identify and understand the corals’ response to heat stress conditions and to pinpoint master regulatory genes involved in coral bleaching due to global warming and climate change. He and his team will use a novel gene-editing tool as a resource to knock down some gene functions with the goal of boosting the corals’ abilities to survive.

A professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology, Bhattacharya’s commitment and efforts go beyond the oceans and the labs.

His goal to help save the corals also inspired him to create a video recently awarded as Best Trailer in the Kiez Berlin Film Festival: The coral holobiont response to climate change. The production of this video is also part of his ongoing “coral hospital” initiative.

“Heat stress is becoming more common due to climate change that is warming the world’s oceans. Coral bleaching leads to reef loss on a global scale. By studying coral biology after gene knockdown, we can figure out gene functions in these animals,” said Bhattacharya.

He added, “First, we need to identify the most important genes related to the thermal stress response, and then we can see if editing or manipulating how these target genes function can help corals be healthier under climate change. This approach will allow us to find both known and new-to-science genes that evolved in corals or the so-called ‘dark’ genes involved in coral resilience.”

Bhattacharya’s research, aiming to regenerate and conserve coral reefs includes PIs Nikki G. Traylor-Knowles from the Rosenstiel School of Marine & Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Miami and Phillip A. Cleves from the Carnegie Institute for Science in Baltimore, MD. Traylor-Knowles and Cleves, who developed a gene-editing tool for corals, also received funds from the NSF as part of the collaborative research project called: Edge CMT: Polygenic traits of heat stress phenome in coral “dark genes” from genome to functional applications.

Courtesy of Debashish Bhattacharya.

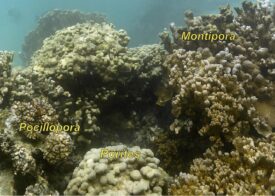

Samples from three different coral species will be collected in the Hawai’i, Australia, and the South Pacific areas, and will be grown under normal and heat stress conditions. The team of researchers will identify the top genes to be knocked out in the next two years.

“We are going to Hawai’i in May to the Kewalo Marine Laboratory, which is part of the University of Hawai’i, to work with Bob Richmond and conduct research in his modern tank facility. We are going to use CRISPR-Cas9 tools, one of the biggest innovations in genetics. When you identify a gene that you think is important in a function as the heat stress, there is a way to target the gene and knock it out or down so that the DNA with those mutations no longer functions. It is a great way to remove or reduce gene functions,” explained Bhattacharya.

Other experiments to be developed include single cells transcriptomics to look at how individual cells express genes.

According to Bhattacharya, coral reefs — also called “rainforests of the sea” — are some of the most biodiverse ecosystems in the world, housing about 25% of all marine life and supporting an estimated one-half to one billion people living in coastal communities. They also provide income and food through sustainable fishing, tourism businesses, and protect coasts by mitigating wave surge. But a big problem that needs to be addressed, per the researcher, is that many coral reefs affected are next to poor countries or isolated island nations.

In June of 2017, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Convention released its first global scientific assessment about the impact of climate change in coral reefs and predicted that “all 29 coral-containing World Heritage sites would cease to exist as functioning coral reef ecosystems by the end of this century,” unless the CO2 emissions are reduced.

The report establishes that the economic, social, and cultural value of coral reefs is estimated at US$1 trillion.

As part of Bhattacharya’s message about the existential and moral importance of corals on the planet and in people’s lives, he and his team continually look for other ways to spread the word about how critical it is to conserve coral reefs.

Courtesy of Debashish Bhattacharya.

“I grew up in Nova Scotia, so I have had a long-term love affair with oceans, both temperate and tropical, particularly in coastal regions where life is abundant. During a trip to Germany to visit my wife’s family, we came up with the idea of using original animated videos — like the one on the coral holobiont response to climate change — focused on science projects in my lab. This led me to writing the script, my nephew Leander Ruemmele and his team to do animations, and to work with my daughter, Lydia, on the voiceovers, and my brother-in-law, Stefan Ruemmele, to compose the original background music,” added the scientist.

“We are also excited about the recent award from the Kiez Berlin Film Festival and the Mannheim Arts and Film Festival for our coral video. It has also been gratifying to see that the video was selected to participate in the 2022 Toronto Short Film Festival. In Hawai’i, we will create new videos and plan animated pieces to explain our research work and introduce the Rutgers-Kewalo team for a future short film on coral conservation.”

This article first appeared on Rutgers Research.