Inspired by SEBS Professors

By Leslie Garisto Pfaff

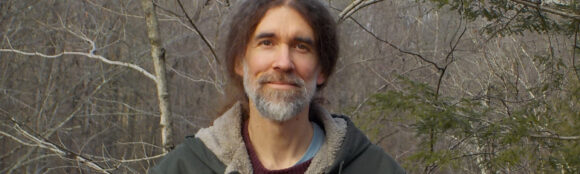

Jay Kelly’s earliest memories are of playing in the woods near his home in Middletown, New Jersey; he says he can’t remember a time when he wasn’t enchanted by nature. Today, his natural playground is much larger, encompassing the coasts and forests of New Jersey and beyond. An ecologist and professor of biology at Raritan Valley Community College, Kelly RC’98, GSNB’06 studies the Garden State’s rare and threatened native plants and is helping to protect and restore them.

Consider American chaffseed, a hairy little plant that bears tubular purple flowers and lives in the Pine Barrens. It’s been listed as a federal endangered species since 1992 and is so rare that by the year 2000, its entire Northeastern range was limited to a small stand growing on the verge of a road in Brendan T. Byrne State Forest.

Conservationists had been unsuccessful at growing it beyond that roadside until 2001, when Kelly, then a Rutgers graduate student, began monitoring the tiny chaffseed colony for the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection’s Office of Natural Lands Management. The plant is a “hemiparasite,” relying on other plants early in its life cycle, but little more was known about its biology. Kelly discovered that chaffseed preferred a nearby plant—the Maryland golden aster—for nutrients, and began cultivating it in a greenhouse alongside the asters. In 2006, he started transplanting seedlings into the wild; most of those transplants are still alive and thriving today, a result Kelly calls “an incredible turnaround for the prospects of the species’ recovery in the state.”

The seabeach amaranth—a low-growing beach-dweller that looks a lot like spinach—also owes its successful comeback to Kelly and his colleagues. It disappeared from New Jersey in 1913 but was spotted growing down the Shore in 2000. In 2001, the Office of Natural Lands Management hired Kelly to survey this species as well. For eight days, he walked 120 miles of coastline from Long Branch to Cape May, sleeping on the beach to save time and gasoline—a task he repeated annually for six years.

He determined that human activities—particularly driving on the beach (which is allowed in Island Beach State Park and some New Jersey towns) and beach-raking—were the greatest threats to the species. So, in 2008, he and his students at Raritan Valley Community College fenced off a portion of the upper beach at Island Beach State Park to see if that would afford sufficient protection to encourage the amaranth’s spread. It worked, and in 2016, they partnered with the Pinelands Preservation Alliance to expand protection along the coastline. The project has been extremely successful: last year, the number of amaranth plants in the state increased by 600 percent.

But few of New Jersey’s 339 endangered plant species have experienced such a dramatic rebound. Although habitat destruction is the primary cause of extinction in much of New Jersey, Kelly attributes these declines to two other factors: an unchecked deer population, responsible for a 70- to 80-percent decline in the forest understory during the past 70 years, and the growing number of invasive foreign species that choke out native plants.

Kelly is a fervent defender of the state’s indigenous plants. “They have a right to exist independent of the benefits they provide us,” he says. “They were here long before we were, and we have an obligation not to diminish the riches of this world for the generations that come after us.” While he’s an avid researcher, he derives his greatest satisfaction from seeing his research translate into successful recovery.

He’s currently monitoring bog asphodel, a plant that grows nowhere in the world but New Jersey, and helping to restore its habitat. He’s also conducting statewide surveys of many of the other 800-plus rare and endangered plant species in the state and working with the Partnership for New Jersey Plant Conservation to strengthen protections for rare plants.

Rutgers provided the fertile ground that allowed Kelly’s lifelong passion for nature to grow and flourish. Thanks to faculty members like forestry professor John Kuser GSNB’76 and plant ecology professors Jean Marie Hartman, Joan Ehrenfeld, Steven Handel, and Jim Quinn and their awe-inspiring field trips to New Jersey’s wild places, Kelly changed his career path from pre-med to ecology and conservation. Those trips, he says, “opened up a world of wonder and magic that I found enthralling and addictive, and I was just hungry for more.” His appetite has been a boon to both the state and to the native plants that call it home.

Originally published on the Rutgers University Alumni Association website.