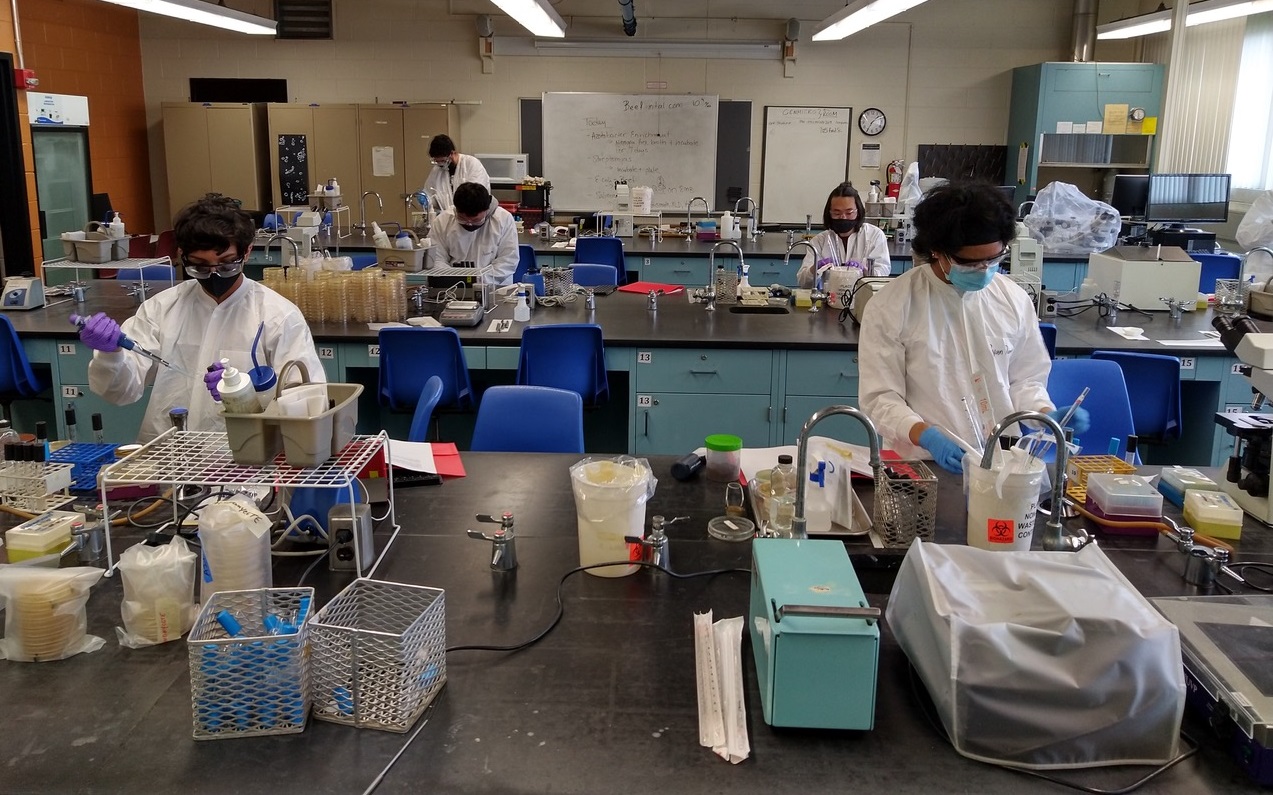

Students in the lab in the Applied Microbiology course. Front row, L-R: Amit Ganguly SEBS’21 and Ryan Dumlao SAS’21. Middle row, L-R: Justin Melgazo SEBS’21 and Hyoung-Joon Kim SEBS’22. Back row: Ahoura Minaeian SAS’21.

The School of Environmental and Biological Sciences (SEBS) prides itself on giving students an education beyond the classroom. Living labs such as the Cook Farm, where each type of animal has its own practicum course, and the more familiar-looking laboratories (think petri dishes and pipettes) offer experiential learning outside of a traditional lecture hall. During the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual learning has helped SEBS students continue their coursework in safe surroundings. However, when conducting hands-on research is a highlight of a student’s time at SEBS, this pivot to interacting via computer screen is an adjustment for many.

For the fall semester, a very limited number of courses were approved by university administration to take place on Rutgers campuses. According to Dean of Academic Programs Thomas Leustek, SEBS currently has the largest number of undergraduates enrolled in face-to-face instruction of any school at Rutgers University–New Brunswick. Of the 346 classes offered by SEBS this fall, 10 are being taught in-person.

One such course is Applied Microbiology in the Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology. At first glance, you might think that not much is different on lab days from before March 17, when Rutgers switched to remote instruction. Then and now, students could be found wearing protective coats and goggles, as safety is a constant priority in a laboratory environment. Where gloves were once optional depending on the experiment, they are now mandatory, as are face masks. Another marked difference to Distinguished Professor and department chair Max Haggblöm and fellow course instructor Ines Rauschenbach is the smaller class size. About half the usual number of students is permitted in the lab.

Teaching Assistant Chloe Costea SAS’17 speaks to Justin Melgazo SEBS ‘21 in the foreground. L-R, in the background: Nelson Jines SEBS’21, Hyoung-Joon Kim SEBS ‘22, and Kayla Aksan SEBS ‘21.

Rauschenbach, who is the Director for the Undergraduate Program in Microbiology, outlines how much hard work and ingenuity goes into coordinating an in-person lab experience this fall. “During a regular semester, the students would work independently. They obtain their own materials, set up their own workstations and many times work in small groups. With the regulations and policies for social distancing, we set up all workstations before the lab so that the students don’t have to move around the room too much. I also adjusted the order and number of the experiments and the time that the students work in the lab. I had to omit our beer brewing lab (a favorite among our students but unfortunately not possible with social distancing) but added a kitchen fermentation experiment where students prepare a fermentation product (such as yogurt, kimchi, hot sauce, or Bulgarian kvas) at home to then isolate the microbes in the lab.”

Amit Ganguly recognizes the unique privilege of attending a class on campus during this highly unusual semester. “I am currently part of the in-person Applied Microbiology lab. I also am part of the online Biochemistry lab, and that provides a helpful point of reference. Being able to attend the lab in person rather than via simulation is more engaging and more conducive towards understanding the techniques employed in the lab.”

When deciding which classes would be submitted for in-person instruction approval, SEBS administration weighed the practical research priorities. Dean Leustek asserts, “Many lab classes can be taught remotely through video demonstrations, but some courses absolutely need to be taught in-person. Imagine learning how to handle a horse through a video. Would anyone be confident approaching a real horse after only watching a video of how it’s done?”

L-R: Alejandra Barnes SEBS’23, Molly the horse, Payton Sweetman SEBS’23.

Alejandra Barnes is a student in the “Animal Handling, Fitting, & Exhibition Supervisors” class in the Department of Animal Sciences, and can attest to the need to work directly with the horses. “If this course were to be given online, I would not be able to learn by making mistakes,” she says.

“Usually we don’t offer this class in the fall,” notes Carey Williams, an equine extension specialist and professor who teaches the horse supervisors class. “We created this for the fall to help get more students into hands-on classes without overloading the barns. We had to make sure that these students didn’t overlap with any other classes, like ‘Horse Practicum,’ going on in the barn at the same time.”

Williams and her students always wear face masks and follow hand-washing and social distancing protocols. “Dr. Williams does an amazing job at making sure we are all safe while learning how to work with the horses,” says Payton Sweetman. In addition to flexibility on the part of the SEBS faculty, students have also made compromises. Sweetman used to live in a Rutgers residence hall during the school year, but most buildings were closed temporarily to prevent the spread of COVID-19. “I now have to drive an hour to get to campus, but it is definitely worth it. I look forward to this class every day.”

In many cases, there is no substitute for the expertise that students attain at SEBS through an experience-based education. “Skills that are essential for people in the animal science field to learn—animal restraint, palpation, observing real-time behavior, and many more—need to be practiced in person to gain confidence and competence. No matter how advanced technology becomes, it cannot replicate how a real, living animal feels and behaves,” states Francesca Buchalski, who is in the pre-veterinary track at SEBS.

Francesca Buchalski SEBS’22.

Ryan Dumlao, a member of the Applied Microbiology lab, illustrates how there is no comparison to the physical lab experience if students want to prepare for life after graduation. He states, “The simulations may offer technical knowledge and demonstrate typical procedures but fail to give students the critical thinking needed to execute lab procedure in a work environment. If something goes wrong with your experiment, you cannot reset and repeat it. There is no hand holding in an in-person lab and students need to become more independent since close contact communication is trying to be minimalized.”

Felicia McCloskey is a Senior Research Animal Worker in the Animal Care Program and has adapted from teaching “Swine Practicum” during a typical semester to the “Animal Handling, Fitting, & Exhibition Supervisors” class this fall. She observes, “You can watch videos and discuss different methods of handling. However, you can’t truly learn how to handle that animal unless you are physically doing it and applying the information you learned to that experience. Students are learning their normal behaviors and that skill will help them identify if that animal is showing a sign of distress.”

“My most difficult struggle was putting myself in an environment with other people,” McCloskey continues. “I had been very cautious about interacting with other people outside of my household. While we are taking all precautions during this semester, it was still a big change for me. I do believe the students are excited and grateful for the experience that they are getting this semester. They have expressed their struggles with remote learning and enjoy the opportunity to take an in-person class. So even though it was a difficult change for me I am so happy that we could offer this for them.”

Students in McCloskey’s course appreciate the sacrifices that SEBS faculty members have made to offer in-person research time. “My instructor has done a great job,” according to Viviana Londono. “We ask and answer questions just like usual, and we are still able to get everything out of the class while being socially distant. At the farm we are able to work with the pigs in separate pens which allows us to get the hands-on experience in a safe way.”

L-R: Viviana Londono SEBS’21 and Ralphael Tencza SEBS’22.

The benefits of face-to-face instruction, when organized safely on campus, cannot be overstated. Not only are students getting ready for their chosen careers, but they are also receiving positive boosts to their well-being and their outlook during these stressful times. Francesca Buchalski shares that, “Being on campus for my farm classes has been excellent for my mental and emotional health: being outside, stepping away from the computer, communicating face to face with my professors and classmates while staying socially distant, and exercising different parts of my brain has helped me to stay positive and focus better in my other, online classes.”

“I feel as though obtaining the ability to work with the farm animals this semester has given me more motivation, determination, and desire to accomplish more,” says Ralphael Tencza, a fellow student in the swine handling course. “Last semester after suddenly transferring to an online platform, I was devastated that I could no longer be on the farm to learn and experience all of the benefits you receive when working closely with animals as well as fellow students. I was determined to take advantage of being able to go back to the farm so that I could continue to do what I love and apply it to everyday life.”

Zahra Fallah echoes these sentiments of how important returning to campus has been to her. “This class has provided some sort of sanity and ray of hope for my future. As I am planning on attending veterinarian school post-graduation, every bit of experience makes a difference. I feel as though there is at least one class where I am 100% engaged and taking away crucial information as a result.”

L-R: Viviana Londono SEBS’21, Ralphael Tencza SEBS’22, Zahra Fallah SEBS’23.

Experiential learning at SEBS is part of what attracts incoming students such as Francesca Buchalski to Cook campus from the start. She says, “When I was touring colleges in high school, SEBS blew away the competition. Having a farm right on campus—and having access to those essential hands-on learning opportunities on the farm as early as freshman year—was the deciding factor for me when it came to selecting Rutgers.”

Payton Sweetman agrees. “I knew SEBS was the right education choice for me when I saw all the animals and heard about all the opportunities that are offered. The amount of students from Rutgers that made it into veterinary school is really impressive. I wouldn’t have these opportunities anywhere else.”

As the Rutgers community remains vigilant and adapts to the uncertainty that the coronavirus brings, there is a shared hope that all classes will soon return for in-person instruction. Until then, grateful participants in the 10 SEBS courses approved for this purpose will make the most of their valued time in the labs and on the farms on the George H. Cook campus.