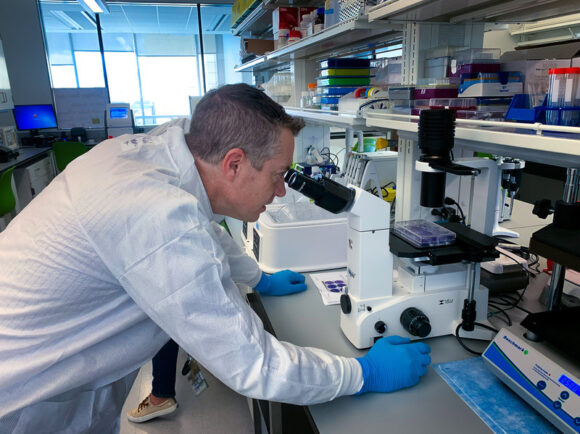

Virologist Christopher Mores looks at cells that have been infected with the coronavirus as part of an effort to develop an antibody test. Photo by Melissa Block, NPR.

As the novel coronavirus continues its global rampage, scientists around the world are racing to stop its spread.

Dozens of projects have been launched under great pressure to deliver a vaccine as quickly as possible.

Among the virologists trying to unlock the pathogen’s secrets is Christopher Mores, the director of a new lab devoted to the research of highly infectious diseases. It’s part of George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health in Washington, D.C.

“I’ve always liked the idea of hunting the thing that wants to hunt us,” Mores says.

He got hooked on the study of infectious disease by happenstance when he was a sophomore at Rutgers University. He couldn’t get into a class he wanted to take, so a buddy suggested he sign up for microbiology instead. The course was taught by the late Douglas Eveleigh — “a totally electric professor,” Mores recalls. “He just got into me and totally excited me about the world of microbes. Within a couple of classes, I was like, ‘that’s what I’m doing.’ And I’ve done it ever since.”

Mores’ work over the decades since has brought him up close to a lot of dangerous viruses: Eastern equine encephalitis. West Nile. Dengue. Chikungunya. Zika. Ebola.

Now, his attention is entirely focused on this latest microbe of mystery: the new coronavirus.

“The speed with which this thing wrapped itself around the world has just been remarkable to behold,” Mores says. “That was shocking for me, to see how fast it went.”

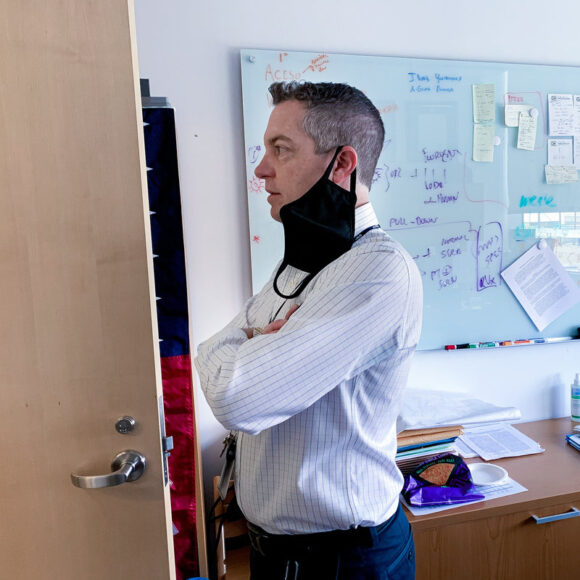

Christopher Mores in his office at the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University. Photo by Melissa Block, NPR.

Mores’ lab opened up for research on March 24, when COVID-19 cases were spreading quickly throughout the U.S. The urgency of the epidemic made it clear that he and his team should scrap the chikungunya research they had originally planned. Now they devote all of their time to figuring out this new virus.

“There’s a tempo and a challenge there,” Mores says, “with stakes that you can sense, at least, if not see. It’s compelling and it’s cool to be in that fight.”

Mores typically works 14-hour days, fueled by a constant infusion of coffee. He leads a team of six research associates and graduate students who are throwing everything they can think of at the coronavirus.

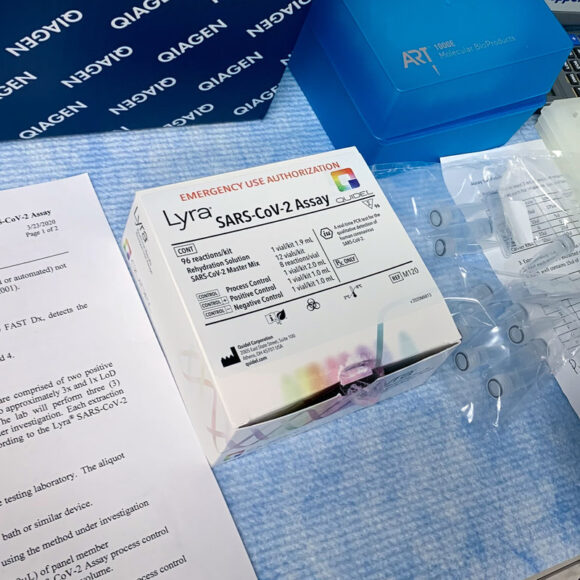

Mores is in talks with biotech companies to help test the effectiveness of eventual vaccine candidates. In addition, his team is working on diagnostic and antibody tests.

The way he describes this work, it sounds like a chess match: “How do you figure out what [the virus] is gonna do, and your best move against it, in real time?” he says. “That’s what an outbreak gives you.”

Mores says he’s always looking for the virus to screw up, to show him something that he needs to defeat it. He gives this pathogen credit: It has proved itself to be a wily adversary.

“There’s plenty of viruses that are far deadlier,” Mores says. “But it’s still a very dangerous virus, and it’s wildly transmissible. Wildly transmissible. And so, this thing’s pretty darn good.”

Mores’ team evaluates a new diagnostic test for SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus, in its clinical lab at the George Washington University Hospital. Photo by Melissa Block, NPR.

What’s stunning to think about, he says, is that something so genetically simple has managed to bring the planet to its knees.

“It’s such a tiny piece of nucleic acid. It’s infinitesimal compared to the size of the human genome, and yet it can just totally unravel us,” he says. “Those are the things that really give me pause sometimes. Like, wow, how could this thing with so few genes, and so little room to move, figure us out so well? I don’t know. I think that’s worth respecting.”

Every day in his work, Mores is reminded of the urgency of this fight.

The virus, he says, “doesn’t care. It’s just doing its thing. It’s just replicating its RNA.”

The challenge for scientists, he says, is this: “Can we be smart enough to see what it’s made of, and what is this going to do to us, before it just goes full bore and takes full advantage of every one of the people on earth it can get into? It’s up to us to figure it out. It’s a puzzle.”

It’s not the pandemic itself that’s surprising, Mores says. After all, experts have predicted an outbreak like this one for years.

What is surprising, and really depressing, is our response.

“A complete failure,” Mores says. “There’s no putting lipstick on that.”

“I see [the coronavirus] as an adversary,” Mores says. “I think it’s compelling and it’s cool to be in that fight.” Photo by Melissa Block, NPR.

As we plot our way forward, Mores says, it’s crucial that we remember the hard lessons learned along the way.

“We want to get back to normal. Absolutely,” he says. “Everybody needs to go back to school, back to work, back to whatever the hell they did before this. But it can’t be to the point of amnesia. We have to still hold some of these scars close and say, ‘Let’s not have this happen again.'”

Because if there’s one thing we do know, Mores warns, it’s that this won’t be the last outbreak we’re going to have to confront.

Editor’s Note: Christopher Mores (CC’95) was featured in an article by NPR, originally heard on Morning Edition.