The Administration Building (center) of the Rutgers College of Agriculture, now known as Martin Hall, flanked by Bartlett (left) and Thompson Halls, circa 1920s.

Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, is the state’s largest institution of higher education and its land-grant institution. Beyond the campus-based academics, there is a component of Rutgers that is solely dedicated to serving the needs of New Jersey residents through research and outreach. Known as the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station (NJAES), and its unit of Rutgers Cooperative Extension (RCE), it has been addressing the needs of New Jersey residents, communities and businesses since it was established in 1880. Despite NJAES and RCE’s presence and impact across the state, we’ve often been dubbed “New Jersey’s best kept secret.” Our mission to change that is through telling our stories – how RCE programs change people’s lives, how communities and businesses have been enriched through Extension services, and beyond. But first, back to the beginning of our story…

Ingrid Nelson Waller smoothed her bobbed hair, adjusted her silk stockings and then strode down the hall of the Administration Building, accompanied by the echo of her T-strap pumps clacking on the wood floor. She entered the director’s office, where she was warmly greeted by her two former gentlemen colleagues simultaneously exclaiming, “Mrs. Waller!,” rising to shake her hand and offer her a chair.

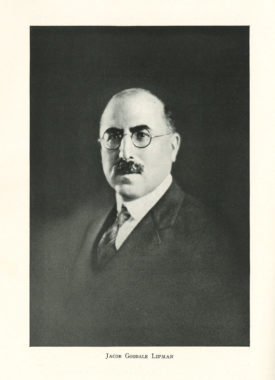

It was 1929, and Waller, who had worked as associate editor for the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station following the first World War, but since left to raise her young family, was meeting with NJAES director Jacob Lipman, and her former editor colleague, Carl Raymond Woodward, who was now assistant to the president of Rutgers University.

Lipman, in shirtsleeves and tie, leaned back in his sturdy wood desk chair, puffing his cigar. Woodward, in suit and tie, sat with hat on his lap and extinguished his cigarette in the ashtray next to his chair.

“As you know,” said Lipman, “we are on the eve of the Experiment Station’s golden anniversary, and I’ve asked you both here to resurrect your roles as editors to document the first fifty years.”

The trio proceeded to discuss the need for a comprehensive review of half a century of the Experiment Station’s work. Waller conjured an image in her head of the mountains of research material they would have to devour. Woodward lit up another cigarette and blew a long, drawn out exhalation of smoke, indicating he was thinking the same thing. While the duo accepted the assignment of such an alluring prospect, they nevertheless were mindful of its exacting demands.

After Waller left the meeting, she pondered over in her head, “How to tell the story of the Experiment Station – how to cover all the work from each department, by each researcher, through the expanse of fifty years?” How indeed?

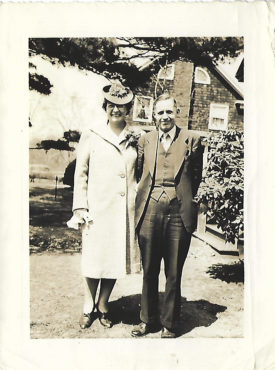

Ingrid Nelson Waller and husband Allen G. Waller, NJAES agricultural economist. Ingrid’s father Julius, and brother Thurlow were NJAES biologists whose work contributed greatly to NJ’s oyster industry. Circa 1940s. Courtesy of the Waller family.

Three years later, the duo released their tome–a 645-page volume–year-by-year account of every experiment and development in each department during the fifty years. Upon its publication, Waller admitted, “The task has been just as difficult as anticipated and even more fascinating. It took but a brief excursion into source material to make us abandon the original idea of a popular narrative, in favor of a year by year account of experiment and experimenter.”

Had they succeeded in telling the story of the Experiment Station? Waller was optimistic on their accomplishment, “In this we entertain the hope that the book will become not alone a history, but a reference work growing more valuable as the years advance.”

And so, New Jersey’s Agricultural Experiment Station 1880 – 1930, by Woodward and Waller established itself on library shelves as a reliable source of dates and data.

Twenty five years later, Waller smoothed her pageboy, adjusted her nylons, and strode down the same hall in the Administration Building, in her practical leather pumps, with matching belt and handbag. She entered the director’s office to meet with William Martin. His predecessor, Jacob Lipman had passed away in 1939, and Waller’s old colleague Carl Woodward had since moved on to serve as president of University of Rhode Island.

Martin, a tall, strapping man, bore a slight resemblance to film star John Wayne. He warmly greeted Waller and thanked her for returning once again from her duties to family and home to help out the Experiment Station.

“Mrs. Waller, as we anticipate the 75th anniversary of the Experiment Station, I am asking you to again create a documentation of its history,” said Martin, leaning forward on his desk with an earnest look. “The first book was quite an undertaking–645 pages! Now I know it’s a lot to take on without Dr. Woodward’s noble assistance, but we’re looking at twenty five years of work this time–not fifty! And, here’s the kicker–I’d like you to bring the history up to date in a short popular book, which would also serve as an anniversary memento.”

Waller let out a sigh of relief–she hadn’t realized she’d been holding her breath. “Dr. Martin, certainly the first volume’s usefulness as a reference work has been realized to a gratifying degree, but,” she added with a twinkle in her eye, “even the staff members, with few exceptions, have admitted–somewhat sheepishly–that they had never really read it from cover to cover.”

She accepted the assignment with mixed emotions–anticipation at being once more a part of an institution which she admired so wholeheartedly, and trepidation at the magnitude of the job.

After the meeting, Waller pondered, “In tune with all that has changed and expanded so drastically in the state and the Experiment Station, to do complete justice to the history of the last quarter century seems a monumental job. Nothing short of a junior-sized encyclopedia could list all the research undertaken and accomplished through these twenty-five years!”

Good on her promise to Dr. Martin, Waller set to work–but this time summoned her story-telling skills. She focused on select stories from across the disciplines and wove an engaging narrative. In 1955, Where There Is Vision: the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station 1880-1955 was published.

Good on her promise to Dr. Martin, Waller set to work–but this time summoned her story-telling skills. She focused on select stories from across the disciplines and wove an engaging narrative. In 1955, Where There Is Vision: the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station 1880-1955 was published.

And so, in brave fashion, Waller didn’t just report dates and data, but invited readers to a enjoy slice of the Experiment Station’s pie. Her tantalizing recipe featured some of the most notable achievements such as the release of the world-renowned Rutgers tomato in 1934, and the discovery of streptomycin in 1943. Albeit, there were some dry parts–the subject being scientific research and all–but Waller was skilled at her craft, and made sure to engage the reader in understanding the relevance of the work and the motivation and challenges of the researcher.

A lifetime later–it was 2019 and the summer was coming to an end. Cindy Rovins finger-combed her unruly curls in the restroom mirror and then strode down the hall to her office in the administration building–Martin Hall on Lipman Drive–her suede flats silent on the faux-wood laminate floor. She slid behind her computer in the Office of Communications and Marketing and clicked through her emails.

A message from the director of Rutgers Cooperative Extension announcing a new RCE Communicators Fellowship Program caught her eye. The program’s goal was to enhance communications and would be led by some organization called The Goodman Center. Rovins had noted that since Brian Schilling had become the new Extension director, he had been stressing that we need to tell our story better. She clicked on the link for The Goodman Center and watched a YouTube video of the director Andy Goodman addressing a group of communicators from non-profits. He was telling them they had great stories to tell and it wasn’t through tedious PowerPoints with charts and graphs of impacts and outreach numbers. It was through telling the personal stories through the eyes of someone involved with their program.

“Yeah!” thought Rovins, “Extension is embracing a culture of storytelling – sign me up!”

“Yeah!” thought Rovins, “Extension is embracing a culture of storytelling – sign me up!”

Sure, the Experiment Station had multiple venues of communicating the research, awards, outreach, impacts and programs through on-line reports, web pages, Newsroom, social media and newsletters – but they rarely took the form of a compelling story or made an engaging read. As agricultural communications editor, she had attempted her own version of storytelling by producing a series of stories in an online newsletter Whats in Season from the Garden State–delving into the Experiment Station’s history and aligning it with the present-day work. Her copies of her predecessor Ingrid Nelson Waller’s books were filled cover-to-cover with post-it notes. She had even read Waller’s first book from cover to cover. But other work duties diverted Rovins’ attention, and operating in a sea of scientists who weren’t inclined to embrace “stories,” she tended to other tasks and had put storytelling on the side.

Rovins, along with 29 other Communicators Fellowship colleagues, were plunged into a culture of creative thinking when coordinators Rachel Lyons, 4-H department chair and Janice McDonnell, STEM 4-H agent kicked off the program and conducted an assessment of members’ thinking profiles: clarifier, ideator, developer or implementer. She became aware of new story-writing skills from The Goodman Center’s webinars: creating a protagonist, what barriers they face, how they overcome them, using descriptive details. She noticed the members from various Extension programs had been grappling with how to communicate the enthralling work from their programs, but didn’t know how to go about it. But once prompted on key elements for composing a good story, the narratives came tumbling out – some hesitantly, as people wrestled with unfamiliar skills, and others more boldly, tapping into dormant abilities.

“This is intriguing,” she thought, “long ago my predecessor struggled with telling the story and while so much has changed, here we are after all these years still struggling with the same issue. And yet, despite now having a whole different set of venues at our disposal–the art of storytelling is timeless.” She wondered, “Once the Communicators Fellows’ stories are released, will others in Extension follow suit and tell their stories? How to keep telling the stories of the Experiment Station – all the work from each department, each program, each county?” How indeed?

Written by Cindy Rovins, writer/editor, SEBS/NJAES Office of Communications and Marketing

See more Stories from Extension.