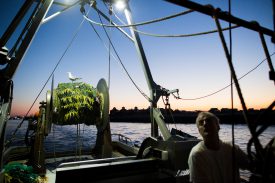

The fishing industry faces antiquated regulations that have been overtaken by climate change, as warming seas force a variety of fish to seek cooler and deeper waters. Photo: Christopher Capozziello, The New York Times.

Editor’s Note: This story originally appeared in the New York Times.

Fish are seeking cooler waters, leaving some fishermen’s nets empty. Studies have found that two-thirds of marine species in the Northeast United States have shifted or extended their range as a result of ocean warming, migrating northward or outward into deeper and cooler water.

Lobster, once a staple in southern New England, have decamped to Maine. Black sea bass, scup, yellowtail flounder, mackerel, herring and monkfish, to name just a few species, have all moved to accommodate changing temperatures.

However, fishing regulations—which set legal catch limits for fishermen—are often based on where fish have been most abundant in the past and these have not kept up with geographical changes.

“Our management system assumes that the ocean has white lines drawn on it, but fish don’t see those lines,” said Malin L. Pinsky, an assistant professor in the department of ecology, evolution and natural resources at Rutgers University, who studies how marine species adapt to climate change. “And our management system is not as nimble as the fish.”

The mismatch between the location of fish and the rules for catching them has pitted recreational fishermen against commercial ones and state against state. It has heightened tensions among fishermen, government regulators and the scientists who advise them and raised questions for fishery managers that have no easy answers.

The center of the black sea bass population, for example, is now in New Jersey, hundreds of miles north of where it was in the 1990s, providing the basis for regulators to distribute shares of the catch to the Atlantic states.

Dean West, above, gets ready to trawl for sea bass and fluke off the coast of Point Judith, R.I. Photo: Christopher Capozziello, The New York Times.

Under current fishing regulations, however, North Carolina still has rights to the largest share. The result is a convoluted workaround many fishermen view as nonsensical. This results in North Carolina fishermen steaming north 10 hours, to where the fish are abundant, to even approach the state’s allocation.

And New England fishermen like Christopher Mr. Brown, whose states have much smaller shares, can legally land only a small fraction of the black sea bass they catch and must throw the rest overboard.

Reflecting these tensions, Senators Richard Blumenthal and Christopher S. Murphy, both Democrats of Connecticut, noted in a letter to the acting inspector general of the Commerce Department in June that fishermen in their state were experiencing “extreme financial hardship” because the apportionment of resources was so outdated. It was suggested that as species of fish move north, the allocation levels should migrate with them.

Such shifts in allocations are possible, but in practice they are difficult to execute.

One approach being actively pursued by scientists and managers is developing methods to incorporate temperature data and other characteristics of the environment into the surveys that regulators use to set fishing quotas.

But even in the best case, trying to estimate the size of fish populations is an uncertain proposition. And the migration of species in response to warming temperatures has made the task considerably harder.

“From a scientific perspective, there are some really interesting questions,” Dr. Pinsky said. “Where did the fish go? Did we eat them? Or did they go somewhere else? Those are questions we haven’t really had to grapple with.”

It remains difficult to determine how much of the dip in a fish population is a result of climate change and how much is a result of overfishing, or even of a natural fluctuation in population numbers from year to year.

A growing number of scientists and managers favor moving eventually to what they call ecosystem-based management, a system that is focused on the environmental niche a species occupies, rather than individual species themselves.

Under such a system, regulation would be aimed at making sure that there are enough fish available to maintain an ecological balance of predators and prey, and quotas might be based on a category of marine species, rather than specific fish. The West Coast has already adopted some version of this approach in the north Pacific, setting an overall quota for ground fish caught in the Bering Sea.

Ideas of property rights and laws are purely land-based, but the ocean is all about flux and turbulence and movement and regulations need to reflect that.