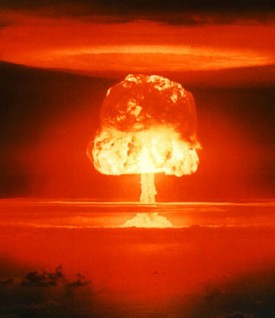

Castle Romeo nuclear test, Bikini Atoll 1954

In a paper published Feb. 6 in the new American Geophysical Union journal Earth’s Future, Rutgers postdoc Lili Xia, Rutgers professor Alan Robock, National Center for Atmospheric Research scientist Michael Mills and colleagues demonstrate how crops in China, the largest grain producer in the world, would respond to the climate changes following a “small” regional nuclear war—using much less than 1 percent of the current global nuclear arsenal—between India and Pakistan.

According to the scientists, such a war could produce so much smoke from the fires ignited by attacks on cities and industrial areas that the smoke would be blown around the world, leading to cold, dark and dry conditions on the ground for more than a decade and producing the largest climate shift in recorded human history.

Using a crop simulation model, the researchers found that in China, in the first year after such a regional nuclear war, a cooler, drier, and darker environment would reduce annual corn production by 20 percent, rice production by 30 percent, and wheat production by 50 percent. These impacts would last for more than a decade, albeit at a gradually decreasing rate, so that even six to10 years after the war, rice production would be down 20 percent and wheat production down 25 percent.

“We were very surprised that even such a limited nuclear war, using only 100 very small nuclear weapons, could produce such a widespread effect on food production,” said Robock, a distinguished professor of in the Department of Environmental Sciences. “The impacts on agriculture would be similar around the world, producing an immediate food crisis, with hoarding and rapid increases in the price of food worldwide,” he added.

As Robock explains, famine and revolution have resulted in the past from much smaller and shorter-lived disruptions in agriculture, such as those after regional droughts or large volcanic eruptions. “The impact of the nuclear war simulated in our study could sentence a billion people now living marginal existences to starvation,” he said.

According to Robock, “the greatest nuclear threat still comes from the United States and Russia, each with thousands of nuclear weapons. Even the reduced arsenals that will remain in 2017 after the New START treaty threaten the world with nuclear winter.”

“The environmental and humanitarian impacts of the use of even a small number of nuclear weapons must be considered in nuclear policy deliberations,” he added.