It was 1943 when Albert Schatz, a doctoral student in Selman Waksman’s Lab at Rutgers College of Agriculture, discovered the soil micro-organism that produced the first antibiotic effective against tuberculosis. As the notoriety around this new “wonder drug” streptomycin grew, Schatz’s initial recognition as co-discoverer disappeared into the background, as all eyes and much of the profits went to Waksman. Schatz faded into relative obscurity.

It was 1943 when Albert Schatz, a doctoral student in Selman Waksman’s Lab at Rutgers College of Agriculture, discovered the soil micro-organism that produced the first antibiotic effective against tuberculosis. As the notoriety around this new “wonder drug” streptomycin grew, Schatz’s initial recognition as co-discoverer disappeared into the background, as all eyes and much of the profits went to Waksman. Schatz faded into relative obscurity.

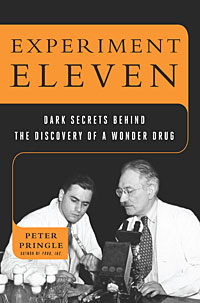

This is the premise in Experiment Eleven: Dark Secrets Behind the Discovery of a Wonder Drug by author Peter Pringle, who reveals much of Schatz’s story. Although it has had some exposure in the media, sixty years later Waksman is still widely recognized as the sole discoverer of streptomycin.

On May 29, the SEBS Book Club met to discuss Pringle’s book, but it was not an ordinary book club meeting in several respects. To start, the location of the session, which was held in the conference room on the third floor of Martin Hall (known as the Administration Building during the streptomycin discovery) was significant in that it may have once been one of Waksman’s two laboratories on the third floor.

Another unique aspect of this meeting was one of the “special guest” participants was a key figure mentioned in the book, microbiology professor Doug Eveleigh. It was Eveleigh who guided Pringle in obtaining documentation at Rutgers while researching the book. What was conveyed in the story was Eveleigh’s historical role in reconnecting Schatz with Rutgers in collaboration with the late Carl Schaffner of the Waksman Institute of Microbiology and Karl Maramorosch, professor emeritus in the Department of Entomology. The ten Book Club participants engaged in a lively discussion with Eveleigh providing a different perspective and additional references on Schatz’s acknowledgment at the time of the discovery than the book portrayed.

As the controversy spanned many years – from a lawsuit against Waksman by Schatz in 1950 to the awarding of the Nobel Prize solely to Waksman in 1952 – Schatz’s estrangement from Waksman, Rutgers and even the scientific community was a veil that cloaked his entire career. It wasn’t until the nearing of the 50th anniversary of the discovery that Eveleigh, with Schaffner and Maramorosch, reached out to Schatz to engage him with the university and the community of microbiologists and to acknowledge his role that was downplayed by the university at the time, in support of Waksman.

Despite Eveleigh’s reaching out to Schatz, and as Pringle notes in his acknowledgements, “Professor Eveleigh patiently assisted me through several scientific thickets, and provided me with contacts and copies of documents from his own archive,” Eveleigh believes that Schatz did indeed receive the credit that was due him at the time.

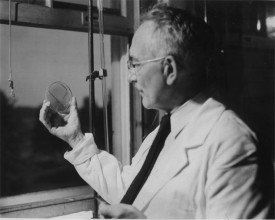

Eveleigh explains, “Professors were treated with high respect in the 1940s and given full credit for the idea of a project, raising the financial support, and developing the methodology, and in this case specifically directing research by screening of the relatively unknown streptomyces microbes. Al Schatz entered this milieu, and was trained in antibiotic laboratory lore prior to being drafted into the army, which resulted in a study in the proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 1943. On being discharged he continued his antibiotic studies, screening and modifying the previously developed methods by reverting to a routine culture medium, and found the two streptomycin producing cultures in 1944. He did no animal work, nor took part in the large scale production which was essential as a basis for the major animal and human tuberculosis trials.” Eveleigh adds that 16 articles of Schatz’s work were published in the open press including Science and the National Academy of Sciences.

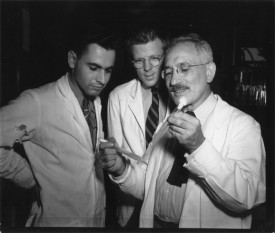

L-R, Albert Schatz, Donald “Monty” Reynolds and Selman Waksman. Reynolds was a graduate student who discovered the antibiotic grisein, which did not work out commercially. Dr. Eveleigh says that Reynolds very much tried to get the two arguing parties onto common ground. Courtesy Rutgers University Archives.

Eveleigh further states, “For proof of success of streptomycin out of the petri dish, Waksman convinced Merck to develop large scale fermenter production while he instigated the animal and human trials in cooperation with the Mayo Clinic. Schatz’s credits lie especially in working with a virulent tubercuolosis strain, and in preparing the batches of streptomycin for the initial animal trials. With this fuller perspective, the reader can decide which of the prime movers merited recognition through a Nobel Prize – Dr. Waksman, Dr. Schatz (the discoverers), Dr. Hinshaw and Dr. Feldman (from the Mayo Clinic who performed the essential human trials).” Eveleigh also pointed out that antibiotic screening was a team approach and that Schatz was the eighth student to join Waksman’s antibiotic screening group.

The book club participants, both faculty and staff members, encompassed research, administration, communications and community engagement departments. SEBS is a scientific school and the role researchers play in discovery and recognition was widely discussed and personal perspectives from working in a scientific setting were shared.

The SEBS Book Club is part of the SEBS Administrative Staff Community Initiative, which offers staff the opportunity to expand their knowledge of the school community and campus and get to know other staff members through a variety of activities such as lunch hour sessions on Get Moving Get Healthy, stress management, Twitter class, campus-wide food drives, bird walks, farm tours and bi-monthly book clubs.

A tentative staff activity includes a tour of the Waksman Museum located in the basement of Martin Hall, which was the laboratory where Schatz made the discovery. An upcoming book club selection is the Alchemy of Air, which additionally explores the theme of scientific discoveries with worldwide impact but resulting in controversy.

Peter Pringle was originally invited to speak on campus about his book Experiment Eleven in November, 2012, but that event, which was cancelled due to Hurricane Sandy, has been rescheduled for October 2, 2013.