Art Wolfe (at right) donated a kidney to lifelong college friend, Chris Zeliff.

Art Wolfe felt like a “human pin cushion.” But he knew extensive medical tests were part of what it would take to ensure he would be a suitable kidney donor for Chris Zeliff, a fellow Rutgers forestry major who lived down the hall from him in his dorm freshman year in 1978. The tests revealed he was a good match.

The kidney transplant surgery took about three hours and required months of recuperation. In addition to scars, Wolfe will have titanium staples in his abdomen for the rest of his life.

But that was not the hardest part of the procedure.

“The most difficult part for me was the worry on my wife’s face, my son crying on my shoulder—the emotions that came to the surface as part of the process,” Wolfe says.

But the best part?

“I gave my friend the gift of life—he gets to live his life again,” he says. “Chris says he’s looking forward to getting back to work. You don’t hear that from 63-year-olds too often.”

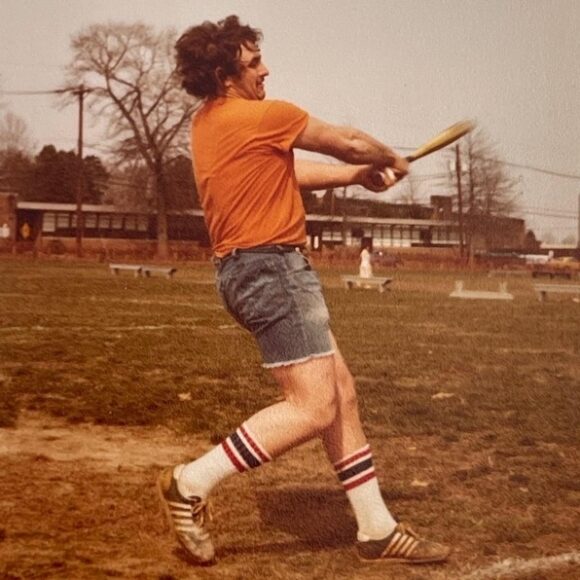

Chris Zeliff CC’83 playing softball when he was a Rutgers student.

Because of dialysis and medications to treat his chronic kidney disease, which resulted from diabetes, Zeliff had been unable to work and was on disability. “When you’re on dialysis, you’re existing, you’re not really living,” Zeliff says. “Some can handle it and still work. I was just wiped every day. Art’s given me a chance to get my life back and not just exist.”

Curt Michael, Zeliff’s college roommate for four years and an international environmental studies major, was deeply impressed with the gift of the kidney and stayed in touch with his long-time friends. “It’s an amazing story,” Michael CC’82 says. “It’s not every day that you save someone’s life.”

Friends from the Beginning

This bond between Wolfe, who lives near Minneapolis, and Zeliff, who lives in East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, formed at Cook College in their dorm, what was then known as Woodbury Hall. Wolfe hailed from Darien, Connecticut, and Zeliff was from Bloomfield, New Jersey. Wolfe chose Rutgers because of the forestry program and Zeliff for its affordability. The pair bonded as forestry majors, attending many of the same classes and working together in the student center cafeteria known as “The Trough,” throwing pizza dough and entertaining their fellow students.

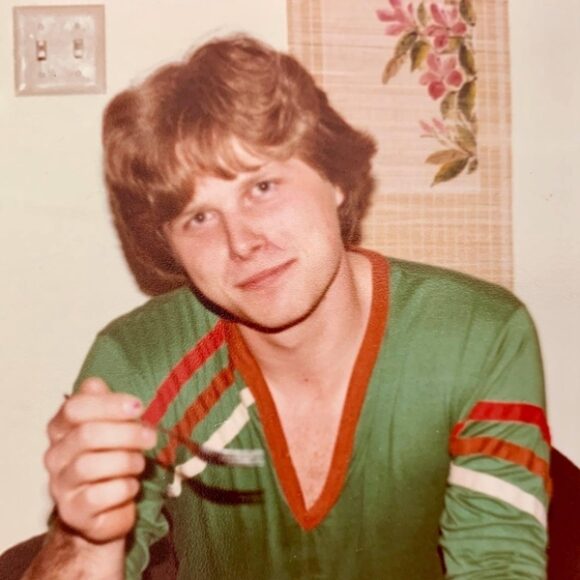

Art Wolfe CC’82 during his Rutgers undergraduate years.

Beyond his student job, Wolfe also received scholarships, enabling him to attend Rutgers. Almost every year since he graduated, he has contributed to Rutgers scholarships, including the Scarlet Promise Initiative.

“I did not come from a well-off family, and I was out of state—two strikes,” he says. “I’m trying to pay it forward because it may not have been possible for me to go to school without scholarships.”

The two loved their time at Cook. “It was a beautiful place to go to school—picture perfect,” Wolfe says. “We participated in sports and made lots of friends. We were Cook students. We loved who we were and took pride in everything we did.”

After graduation, Wolfe pursued a career as an “end-use forester” selling newsprint, and Zeliff worked in hazardous waste management. They kept in touch over the years—calls, cards, visits—despite distance, time, and family obligations. And when Zeliff learned he was in kidney failure, he let Wolfe know. As a universal blood donor, Wolfe told him, “Hey, I’ve got a kidney for you.” Zeliff was researching family members, however, since they’re typically a better match.

This was not Zeliff’s first experience with transplantation. His father, who faced years in a nursing facility, received a bone transplant in his vertebrae enabling him to lead an independent life. His friend’s daughter was killed in a car accident, and while her parents chose to donate her organs, it was a horrific time to have to make such a decision.

“I implore everybody, as long as it doesn’t violate any of your religious beliefs, sign up now to be an organ donor,” he says. “So many people die every day in need of a kidney. You can impact so many other lives.”

The Ultimate Gift

Art Wolfe, left, and Chris Zeliff on fishing trip in July 2023.

In July 2023, the day before the Cook College alumni fish fry they traditionally attend, the pair went fluke fishing in the Raritan Bay, where Wolfe learned the family option wouldn’t work. He saw only one solution. “Art said, ‘Give me the paperwork’,” Zeliff says. “So I gave him a brochure on transplants. He went back to Minnesota, contacted the hospital, and got the ball rolling.”

Wolfe began extensive research. Then came medical tests at Cooperman Barnabas Medical Center, what Wolfe describes as a “a full lube and oil change with complete diagnostics.”

“They wanted to make sure that I—who have lived a life of not always taking the best care of my body in, we’ll say, a social way—was not putting myself at risk,” Wolfe says. “In the end, as far as 63-year-old horses go, they said I’m pretty damn healthy.”

Surgery was set for October 31. The week before, however, Zeliff got COVID, postponing the date to November 15. Both are recovering nicely now—especially Zeliff, who says he had been sick for so long that he didn’t realize how sick he had been. Now he’s looking forward to getting back to work, maybe going fishing in Alaska with Wolfe in 2025.

“We’ve been friends for 45 years and still love each other,” Zeliff says.

This article first appeared on the Rutgers Foundation website.