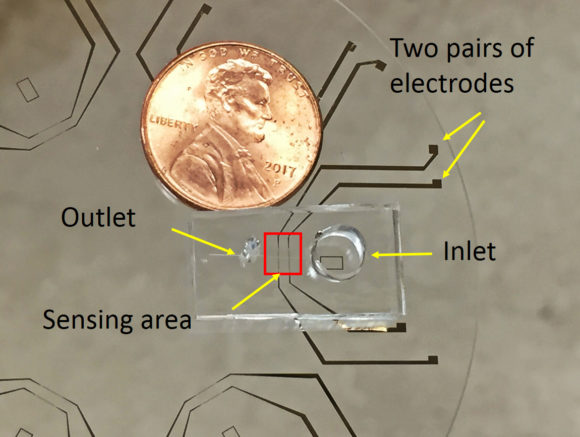

This portable tool can rapidly reveal whether a cell is stressed, robust or unaffected by environmental conditions. Image: Jianye Sui.

Device could be used to find threats to ecosystems

Imagine a device that could swiftly analyze microbes in oceans and other aquatic environments, revealing the health of these organisms – too tiny to be seen by the naked eye – and their response to threats to their ecosystems.

Rutgers researchers have created just such a tool, a portable device that could be used to assess microbes, screen for antibiotic-resistant bacteria and analyze algae that live in coral reefs. Their work is published in the journal Scientific Reports.

The tool, developed initially to assess algae, can determine in the field or in laboratories how microbes and cells respond to environmental stresses, such as pollution and changes in temperature or water salinity.

“This is very important for environmental biology, given the effects of climate change and other stressors on the health of microorganisms, such as algae that form harmful blooms, in the ecosystem,” said senior author Mehdi Javanmard, an associate professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering in the School of Engineering at Rutgers University–New Brunswick.

“Our goal was to develop a novel way of assessing cell health that did not rely on using expensive and complex genomic tools,” said co-senior author Debashish Bhattacharya, a distinguished professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology in the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences. “Being able to assess and understand the status of cells, without having to send samples back to the lab, can allow the identification of threatened ecosystems based on a ‘stress index’ for their inhabitants.”

The research focused on a well-studied green microalga, Picochlorum. The tool can quickly reveal whether a cell is stressed, robust or unaffected by environmental conditions. Microbes pass one by one through a micro-channel, thinner than the diameter of a human hair. Impedance, or the amount an electrical field in the tool is perturbed when a cell passes through the channel, is measured. Impedance varies among cells in a population, reflecting their size and physiological state, both of which provide important readouts of health.

The researchers showed that electrical impedance measurements can be applied at the single cell and population levels. The scientists plan to use the tool to screen for antibiotic resistance in different bacteria and algae that live in symbiosis with coral reefs, which will help give them a better idea of coral health.

The lead author is Jianye Sui, an engineering doctoral student at Rutgers. Fatima Foflonker, a graduate of the microbial biology doctoral program, co-authored the study.

Editor’s Note: this article originally appeared in Rutgers Today.