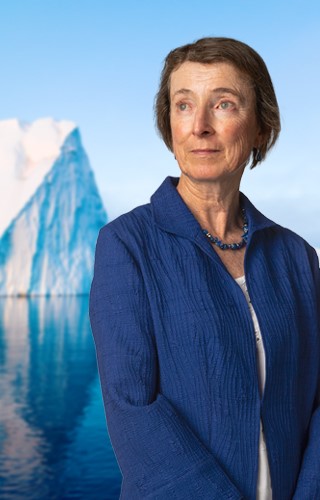

Visiting scientist Jennifer Francis studies the impacts of Arctic ice melt.

Rutgers visiting scientist Jennifer Francis was the first to identify the consequences of shrinking Arctic sea ice

If the world of climate science did not know about Jennifer A. Francis before March 29, 2012, it certainly knew about her afterward. On that day, the New York Times published a front-page story under the headline “Weather Runs Hot and Cold, So Scientists Look to the Ice.” The story explained that certain climate scientists were theorizing that extreme weather patterns in much of the world’s temperate latitudes could be traced to the drastic decline of sea ice in the Arctic –“believed to be a direct consequence of the human release of greenhouse gases,” the Times reported.

And then the story quoted its first source from the scientific community: Francis, a visiting scientist at Rutgers University-New Brunswick who until recently was a research professor in the Department of Marine and Coastal Sciences at the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences. “The question really is not whether the loss of the sea ice can be affecting the atmospheric circulation on a large scale,” said Jennifer A. Francis. “The question is, ‘how can it not be, and what are the mechanisms?’ ”

The story stemmed from a recently published study of the Arctic ice melt and its global implications that Francis had coauthored with Steve Vavrus, a climate scientist at the University of Wisconsin. Their paper theorized that the loss of Arctic ice had caused the jet stream to weaken, in turn causing weather patterns to stall, resulting in droughts, heat waves and other extreme weather events. Soon the Times was regularly reporting on their work, and although many climate scientists questioned the findings – Francis acknowledges it was then merely a hypothesis still in need of further study – it’s fair to say that her life has not been the same ever since. A year later, she was testifying before the U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, and before long she was presenting lectures to the World Bank, the U.S. Navy and the FBI.

Today a prominent community of scientists is exploring the meteorological impact of the Arctic ice melt, and Francis has embraced her role as a public educator, seeking to show how climate change directly affects so many people. “Especially in their wallets,” she says. “They’re seeing insurance rates go up. They’re hearing about Uncle John in Nebraska having no water for his corn. People naturally are questioning what’s going on and why. Being able to answer some of those questions is really, really important, and it’s a huge role that I can play a part in.”

The Rutgers Climate Institute comprises more than 100 distinguished researchers representing 17 schools and programs in the natural and social sciences as well as the humanities. As observers of the natural world, they have been among the first to sound alarms about the potentially catastrophic impact of the earth’s changing climate – from rising sea levels and warming temperatures to severe drought and the proliferation of wildfires. They’ve testified before Congressional panels, received accolades from their peers and are frequently quoted in the news media. This article is part of our series about the Rutgers Climate Institute.

Editor’s note: this article originally appeared in Rutgers Today.