The livestock scene on the George H. Cook Campus has evolved since the university’s first dairy farms conducted research in the 1860s. Today, the Department of Animal Sciences builds on its history working with livestock to bring new opportunities for students and the state.

The livestock scene on the George H. Cook Campus has evolved since the university’s first dairy farms conducted research in the 1860s. Today, the Department of Animal Sciences builds on its history working with livestock to bring new opportunities for students and the state.

Dairy Roots

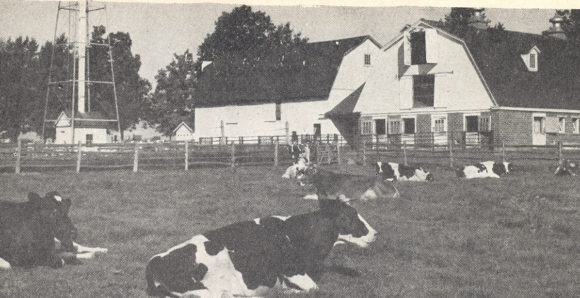

If you visited or attended classes on the George H. Cook Campus, it’s likely you remember the dairy cows along College Farm Road that called the campus home. From 1970 up until 2000 there were around 40 milking cows and 25 heifers housed on campus, while from 2000 to 2017 approximately 80 to 200 Holstein heifers were cared for. And they were a huge part of the student experience for anyone studying in the Department of Animal Sciences.

The farm was, for quite some time, a research hub. A number of faculty with dairy expertise were drawn to the farm to examine topics from improving the efficiency of milk production to optimizing nutrient use, working alternative feeds, and understanding the biology of lactation. As a result, students had the unique opportunity to assist dairy staff with all aspects of care. Karyn Malinowski, now the director of the Equine Science Center, remembers being one of the first female students working with the dairy herd while pursuing her undergraduate degree in animal science. She lived in the dairy boarding house and helped care for the animals. One night, she found herself delivering a huge bull calf in the middle of the night, donning just pajamas and a robe. These kinds of stories are not uncommon for alumni of the Department of Animal Sciences who were drawn to the idea of working with livestock.

Students Sydney Gavinelli SEBS ’19 and Alexander Eldridge SEBS ’21 handling a cow and her week old calf Boo.

The number of dairy farms in New Jersey has decreased sharply over the years. In 1935, the state had over 6,000 dairy farms with 130,000 cows. By 1975, that number had dropped to 47,000 cows on 760 farms.

Currently, there are 6,000 cows on just 79 farms in New Jersey. With this decline in dairy operations, NJAES shifted its focus from the needs of the local dairy industry to initiatives that impact first-time farmers and emerging agricultural production. SEBS in turn began utilizing its animals on the George H. Cook Campus primarily for teaching purposes rather than dairy production and research. Where does this evolution leave the dairy cows of Cook, which was once named a “Dairy of Distinction” by the Dairy Farm Beautification Program?

The animal science major is the largest at SEBS, with more than 450 students enrolled each year in one of five tracks: pre-veterinary medicine and research, laboratory animal science, equine science, production animal science, and companion animal science.

A New Focus

Horse from Rutgers Equine Science Center

The truth is that you’ll still see cows on the George H. Cook Campus. But today’s residents aren’t dairy cows; they’re beef cows. “Moving to a more sustainable pasture-based program with Angus and Hereford beef cattle allows students the opportunity for hands-on learning throughout the life cycle, from breeding and calving to weaning and finishing,” says Wendie Cohick, professor and chair of the Department of Animal Sciences.

Current residents include four adult beef cows, four breeding-age heifers, two young cows aged 1 to 2 years, two four-month-old calves, and one calf that’s just weeks old, with plans to expand the herd as the program develops. In addition to being able to interact with and learn about cattle at all ages, students can apply farm and genetic management skills learned in the classroom to the beef herd.

Things look a little different, too. The beef cows live in the new dairy heifer facility that was built in 2000. And though the dairy cow barns are no longer in use by cattle, you’ll still see them on campus, currently housing the Alpine goat breeding herd.

Students returning pigs to their pens.

The new beef cattle program will continue the tradition of offering farm-fresh products to the state. But this time, instead of dairy, locals will have the opportunity to purchase Scarlet Beef. “We have developed a farm sales program with a considerable amount of student involvement to offer value-added products to the Rutgers community and the public,” Cohick says. “This includes the sale of farm-raised pork; lamb; goat meat; and chicken; composted manure; and goat milk soap.” The farm continues to welcome at least 25,000 visitors each year, including 4-H and Future Farmers of America students who will make up the next generation of Jersey farmers.

The beef cattle program, though still in its infancy, will also form the foundation of future translational research at SEBS. Projects like rotational grazing research and those focused on other sustainable livestock practices, will form best practices to be used by beef farmers nationwide, bringing sustainable foods from farm to table. Would the Cook community have it any other way?

According to the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges, almost half of those who apply to veterinary schools end up attending. At the Department of Animal Sciences about 75 percent of who apply are accepted.

Beyond the Farm

Research in the Department of Animal Sciences continues to address issues that affect the health and well-being of New Jersey residents. For example, scientists are beginning to understand that a predisposition to certain diseases and disorders—from infertility and obesity to diabetes, cancer, and even addiction—can start in the womb. What effect can maternal obesity have on a child’s life? What about fetal alcohol exposure or the impact of exposure to chemicals like pesticides on a person’s health? These questions have the potential to shape future guidelines for prenatal care, and it all starts at SEBS.

Editor’s Note: this article originally appeared in the spring 2018 edition of Explorations.