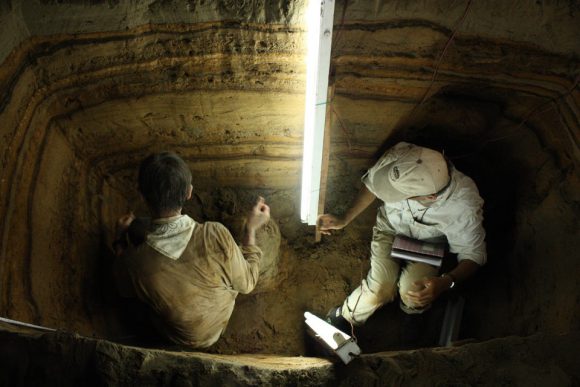

Kerry Sieh and Charles Rubin use fluorescent lights to look for charcoal and shells for radiocarbon dating. Photo courtesy of Earth Observatory of Singapore.

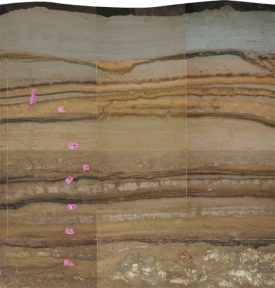

The stratigraphy of the excavated sea cave. The lighter bands are sand deposited by tsunamis over a period of 5,000 years; the darker bands are bat poop. (Courtesy of Earth Observatory of Singapore).

Researchers stand in the trench of a sea cave. (Photo courtesy of Earth Observatory of Singapore.)

Marine and Coastal Sciences professor Benjamin Horton and colleagues have found the key to thousands of years of Indian Ocean tsunami activity in a cave in Indonesia.

After the devastating 2004 tsunami that hit the Indian Ocean, researchers—including Horton—asked themselves if a tsunami of this magnitude had ever happened before and, more important, would it happen again?

They knew the answers would not be found in written or seismometer records, but they could—possibly—be found in sand. Tsunamis pick up sand from the depths of the ocean floor, depositing it on land as the waters recede. And the answers they’ve been looking for have been found in a particular Indonesian coastal cave which contains layers of sand left by tsunamis all the way back to the Stone Age 7,400 years ago.

Read more about this spectacular find in The Atlantic.