Food Science Building with Rutgers 250 banner.

With one professor, one room, and two support staffers, the Department of Food Science opened its doors in 1946 to bring food-related science, education, and research to Rutgers. This year, the department celebrates its 70th anniversary…and its incredible evolution.

Looking back at the history of the Department of Food Science is much like hopping in a time machine and taking a journey through our culture’s relationship with food. In its earliest days—the late 1940s and early 1950s—researchers in the department focused primarily on food processing and canning technology, says professor and former chair Mukund Karwe. Slowly but surely, around the late 1990s and early 2000s, emphasis began to shift onto natural products and the natural functionality of foods (think of the health-boosting lycopene in a tomato for one example). Today, the emphasis has shifted yet again, and this time it’s onto food safety, food microbiology, and nutrition.

Outreach and Research

Outreach and Research

Take it from Donald Schaffner, extension specialist and distinguished professor in the department: bacteria touches everyone. “Bacteria don’t care whether they’re in your kitchen or in a food processing plant,” he says. “The work we do stretches from making sure that the food is safe in your kitchen, to making sure that restaurants, supermarkets, and food processors of all sizes are safe.”

How? One way is through outreach, and as extension specialist, Schaffner knows a bit about that. By working with the Food Innovation Center, Rutgers’ business incubation and economic development accelerator program, Schaffner is able to work with food entrepreneurs. He helps them tackle issues ranging from the finer aspects of microbiology to risk assessment and safety. (The two most common topics? Shelf life and market regulations.)

Food Science class with Prof. Richard Ludescher, dean of academic programs.

Schaffner also works with the Department of Family and Community Health Sciences (FCHS), which is housed at the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station. From county offices, FCHS works to promote healthy families, schools, and communities through collaboration and science-based education, and the Department of Food Science acts as its technical resource. Common questions surround whether food is still safe if it’s left on the counter, how to can safely, or what to do with frozen food when the electricity goes out.

On campus, food science graduate students lend their expertise to the dining halls by conducting microbiological tests and doing health-department-style inspections. “It’s a win-win,” says Schaffner. “The students benefit from it, and the dining halls benefit from it.”

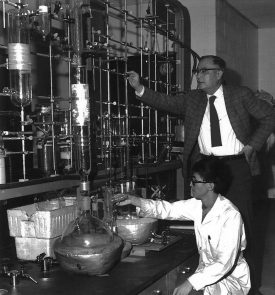

But outreach isn’t the only impact of the Department of Food Science. The department also boasts a rich history of groundbreaking research, in the areas of food biology (molecular genetics, biochemistry, microbiology, and more), food chemistry (applying chemical techniques to the understanding of food, its physical properties, and its chemical transformation during manufacture and storage), and food engineering (manufacturing, processing, packaging, and preservation).

Student Dylan Jagiello (Exercise Science ’16) in the Department of Food Science.

Some of the research focuses on nutritional aspects of food, like the 1992 findings that green tea boasts antioxidant benefits. (Look no further than supermarket shelves stocked with everything from green tea ice cream to green tea powders for proof that this benefit is invaluable in today’s food industry.)

Other research, like a project led in part by food science professors Loredana Quadro and Michael Chikindas, seeks to solve a worldwide nutrient deficiency. Vitamin A deficiency, experienced by hundreds of millions of people worldwide, and mostly in the developing world, is linked to blindness, impaired immune systems, and birth defects. “We came up with the idea of using bacteria instead of food to provide this nutrient which, currently, can only be obtained by ingesting food,” explains Quadro. What they found, in mouse models, was that E. coli bacteria could in fact be engineered to produce beta-carotene, which naturally produces vitamin A. The issue is, of course, that humans can’t safely ingest E. coli. “We are working with a strain of probiotics to generate something that can be accepted safely by humans,” Quadro says. That discovery will be groundbreaking, since it would overcome the need to constantly ingest foods or supplements with vitamin A, and address a deficiency that has worldwide impact.

Looking Ahead

Going forward, the department has a clear and distinct charge: to be an internationally recognized and student-centered program for innovative education and research, focused on global concerns of hunger and obesity.

Its primary focus, indeed, will surely shift yet again. This time, we may see research tackling issues like naturally functional foods that can improve health; the interaction of foods’ microorganisms with soil, water, processing equipment, and human contact; and other collaborative efforts such as those coming out of Rutgers’ newly established Institute for Food, Nutrition, and Health.

And by leveraging New Jersey’s robust food manufacturing and agricultural economy, there’s no doubt the Department of Food Science will continue to facilitate change on the farm and in the lab.

“Food science is alive and well at Rutgers,” says Schaffner. “It really takes this huge team of people with all their specific expertise, working together. I see the department as that connecting piece.”

Editor’s Note: This story first appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of Explorations, a publication of the Rutgers School of Environmental and Biological Sciences.