The seven veterans from Lakewood Veterans Affairs who participated in the pilot study in April 2016.

By Kyle Hartmann

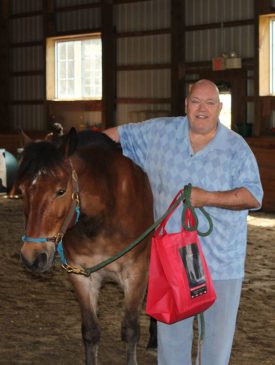

Walter Cooper stands in an enclosed dirt horse arena with Titan, a thousand-pound cross-bred pony that almost overshadows him. A Vietnam veteran from the U.S. Army’s 25th Infantry (1969 – 1970), Cooper can appear to be quite an imposing man himself, but next to a horse almost anyone seems small.

“Any time I spent with Titan during the project was my favorite moment because he seems to understand the issues I have,” says Walter Cooper, seen posing in the arena with Titan.

Cooper was just one of seven veterans who took part in a trial to study the effect of Equine-Assisted Activities and Therapies (EAAT) on the well-being of veterans and horses.

While it is commonly thought that human and animal interactions (such as those seen with therapy animals) have a positive impact on both the human and animal, previous studies have only focused on the impact that EAAT has on people (either a change in demeanor, heart rate or blood pressure).

This study was one of the first trials conducted that focused on not only the human side of this type of therapy, but also how EAAT affects the horse.

Used for the first time since its creation, the Rutgers University Equine Science Center’s Gwendolin E. Stableford Endowed Equine Research Fund covered the costs of not only the five days of the experiment (and an additional day used as a standing control), but also all costs associated with analyzing the various samples and measurements that were collected.

In what might be potentially groundbreaking research for those interested in EAAT as a way to help veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), the fund allowed this pilot study to provide the needed data to show the feasibility of a larger research project.

Karyn Malinowski, director of the Equine Science Center, and Jennifer Tevlin, who holds a Master of Science degree in Animal Science (with a specialization in Equine Science) and a Master of Science in Mental Health Counseling, envisioned this trial as a way to bring together the science from both sides of EAAT. In order to have a comprehensive trial, they needed to create a team with knowledge of all aspects of the activities the veterans participated in.

The team consisted of specialists throughout New Jersey and the northeast, including consultants from Sports Medicine and Imaging in Delaware, Eric Birks and Mary Durando. They took heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV) measurements from the horses using electrocardiogram (ECG) monitors.

The instructors for the sessions, all certified as Equine Specialists in Mental Health and Learning, guided the interactions between the horses and veterans for 60-minute sessions.

These volunteers came from Special People United to Ride (SPUR), a group that was established in 1981 and has since funded the construction of the equestrian center in Lincroft, acquisition of therapy horses, and training of instructors. Rounding out the team were two volunteer nurses who took HR and blood pressure measurements of the veterans.

The team, now assembled, needed a group of participants that could commit to coming every day. It would be important, so as not to skew the results, that each participant could commit to the same days and times for a one-week period.

The veterans with their horses.

A group of seven veterans from Lakewood Veterans Affairs ended up making this commitment, each making their way to the Monmouth County Park System’s Sunnyside Equestrian Center in Lincroft, New Jersey, for five consecutive days in April of 2016.

Sitting on part of the 135-acre site and preserved as open space by the Monmouth County Board of Chosen Freeholders, the Sunnyside Equestrian Center works closely with the community to provide therapeutic riding and activities to people of all abilities.

The co-manager of the facility and program director for SPUR, Jackie West, provided access to the facility and horses, as well as nurses who were from SPUR’s volunteer base.

Each day started with a group meeting between Tevlin and the veterans, who filled out a self-assessment on the first day of the study before any interaction with the horses, while Malinowski and her team from Rutgers (including undergraduate students from the Department of Animal Sciences) prepared to take blood samples from the horses. The samples were used to look at specific markers in the blood, such as the hormone oxytocin, which is frequently described as the love or happiness hormone.

“To our knowledge, this is the first report of the measurement of oxytocin in horses used in EAAT programs,” stated Malinowski. “If the concentration of this hormone increased during the trial, we would be able to suggest a positive correlation between EAAT and the overall ‘happiness’ of the horses.”

The other hormone that was analyzed was cortisol, or the “stress hormone.” An increase in the concentration of this hormone could indicate that the horses were becoming stressed by their interactions with the veterans.

Mary Durando shows Rutgers students how to attach the ECG leads.

After the Rutgers team met, Birks and Durando showed the students the proper method of attaching and securing the ECG monitors to the horses so that measurements could be taken throughout the session.

The readings from these devices allowed the team to look at HRV, or the natural variation in time between consecutive heart beats. In this case, more variation between heart beats indicates a more relaxed state. Conversely, a decrease in variation between heart beats would be an indicator of potential stress.

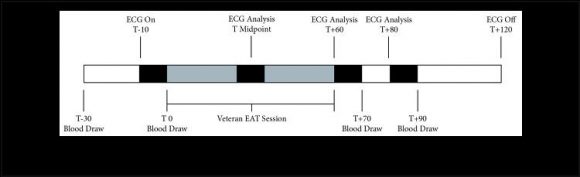

The devices were powered on 10 minutes prior to the EAAT session, stayed on during the hour-long session, and continued to remain on for 60 minutes after the end of the session. This was repeated three times during the study (on the first day of the trial, the last day of the trial, and on the standing control day) and then analyzed by Birks and Durando who specialize in equine exercise physiology and cardiology.

Once the ECG monitors were on, and the second blood draw was completed, Tevlin, as well as the instructors from SPUR, took the horses into the indoor arena where the veterans were waiting. She guided the veterans through various interactions with the horses, which included petting, grooming, and walking, among various other interactions.

During this time the veterans had their pulses and blood pressures taken by the nurses, and on the last day they filled out a self-assessment to identify any psychological changes since the original assessment completed on day one.

On top of the five days of sessions with the veterans, an additional standing control day (the day where HRV measurements and blood were taken from the horses, but the horses did not interact with the veterans) was used to measure the normal physiological concentrations of oxytocin and cortisol in the horses’ systems, as well a control measurement for HRV.

In the weeks that followed, samples were analyzed, results complied, and statistical analyses performed. This work was accomplished with colleagues from Indiana University, Monmouth University, and the consultants from Sports Medicine and Imaging. Finally, almost a year later, Malinowski is able to report her findings.

The schedule for the blood draws and ECG Measurements before, during, and after the Equine Assisted Therapy (EAT) session.

Our study demonstrated that “EAAT resulted in a reduction in HR in horses on both session days, suggesting that EAAT resulted in reduced sympathoadrenal activity in these horses and that the therapy sessions were not perceived as being stressful to the horses,” stated Malinowski. “Coupled with the fact that there were no changes in plasma cortisol, these findings imply that in horses experienced with EAAT, the interaction with PTSD veterans did not result in a stress response.”

The paper, The Effects of Equine-Assisted Therapy on Plasma Cortisol and Oxytocin Concentrations and Heart Rate Variability in Horses and Measures of Symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Veterans, goes on to state that “participants also reported a significant decrease in symptoms of anxiety and depression along with other symptoms of psychological distress and PTSD.”

Because this was a pilot study, Malinowski recommends that further research be conducted with a larger number of horses, and a potentially longer time frame, to study the long-term impact of EAAT on horses used in these types of activities. She would also like to add HRV measurements and blood sampling to the human side of any additional research as a way to better evaluate the interactions between horses and humans.

The study has been published as an open access paper.