Kimberly Tryba is a third-year graduate student in the Department of Landscape Architecture.

By Samuel Ludescher (SAS’18).

Driving along Cedar Lane where it meets Road 1 and the southern border of Rutgers’ Livingston Campus, there is a series of one-story buildings that sit next to the pronounced curve in the road. These buildings currently serve as warehouses and administrative offices for the university. However, their original purpose was far more important and is in danger of being forgotten. Kimberly Tryba, in her third year of the Rutgers Department of Landscape Architecture master’s program, has made it her mission to keep that from happening.

Tryba has been on an extensive research journey to unearth the fragmented history of Camp Kilmer, one of America’s army encampment designed as a staging area during World War II. The camp saw more than three million people walk through its doors, including GIs returning from World War II. It also continued to aid global humanitarian efforts until its decommissioning in the 1950s.

In the practice of landscape architecture, Tryba’s historical research is not just informative; it’s also a powerful design tool. While her research was crucial in understanding the significance of the site, “it is not just about researching Camp Kilmer,” she explains. “It’s also about how the cultural history of a site can inform a design.”

Tryba will consider the present characteristics of the site in her design in a way that capitalizes upon and enhances its assets. The site’s cultural context will help her discern its future narrative. “Landscape architecture is multi-disciplinary, utilizing research approaches that range from the biological and the anthropological to the creative,” she adds.

“When I began this line of study, I challenged myself to see if there was a way that, in our rush towards modernity, we could also honor this layered history without utilizing a tabula rasa approach—literally scraping the existing site features away and starting as a clean slate,” says Tryba. “Ironically, this was the army’s approach when preparing to build Camp Kilmer, as well as that of the original European settlers to this area.”

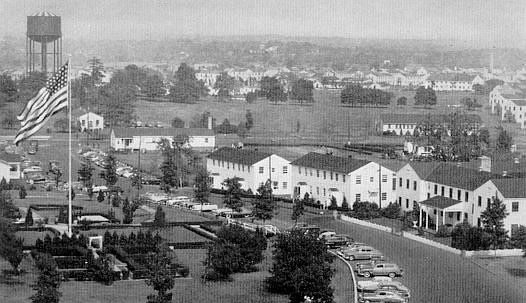

Camp Kilmer Headquarters Building on Right.

Much of Camp Kilmer was demolished following Rutgers’ acquisition of a parcel of land equal to one-third of the camp from the U.S. Army. Today, there are only a handful of indicators on Livingston Campus that signify Camp Kilmer existed at all—one of which is a memorial that was erected when the camp was opened to commemorate Joyce Kilmer, the New Brunswick-born soldier and poet for whom the camp was named. Other than the street names, the only other primary marker of Camp Kilmer is a bulletin board in the Rutgers Ecological Preserve—on the white path adjacent to two berms, or earthen mounds, that mark where the ammunition buildings once were.

Tryba hopes to honor the layered history of Camp Kilmer by recognizing and continuing to use its grounds. Remnants of Kilmer’s military design can be seen in its remaining architecture and infrastructure, like the nondescript buildings propped up next to Cedar Lane that once served as the transportation depot for Camp Kilmer.

“My interest in the site was sparked when I went to take photos of it one day. I was struck by the way that nature seemed to be invading or reclaiming the space,” says Tryba of the former operations and maintenance depots. Her initial approach was to seek “design interventions that might reintroduce natural systems while also capitalizing on the space and structures in a way that embraced the educational mission of the university.”

She thought it was simply under-utilized space and, at the time, had no idea what she had stumbled upon. “I was not immediately aware of its historical significance.” But, once undertaking the research, it became evident to her that the site “could speak to a collective memory the space represents—not only to the university community, but also to those who have a connection to it at another point in its rich history.”

“It’s uncanny the number of times, that on the mere mention of Camp Kilmer, someone has shared with me that a family member passed through it—or had other experiences directly related to the site,” she recalls. Tryba then understood that she needed to dig deeper to truly grasp the entirety of Camp Kilmer’s narrative.

While her research began at Rutgers, it has led her far and wide to assemble the scattered history of Camp Kilmer. During her research on the practice of historical preservation, she came across a few texts that spoke about the notion of ‘palimpsest’ as a means of illustrating such a layered history. The word originated in the literary world, reflecting the practice of reusing manuscript skins to write two or more successive texts, each one being erased to make room for the next – often, with the scraped pigment layers remaining visible. “As such, the concept easily translates to other disciplines,” Tryba says.

This led her to apply the notion of palimpsest as a basis for her research and design intervention, creating a series of land-use maps of the Camp Kilmer-Livingston Campus. These maps were based on aerial photos dating back to the 1930s and data collection conducted by Rick Lathrop, professor in the Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Natural Resources and director of the Rutgers Ecological Preserve, which adjoins the Camp Kilmer site. The land-use maps demonstrate how the area was transformed by tracing “the natural ecology and development of the land from present day back prior to Camp Kilmer’s inception, when the area was predominantly used for agriculture,” she says.

World War II and its cascading events changed many lives. For many, Camp Kilmer represented the start of a new life. Documenting and preserving Camp Kilmer’s history is the first step toward embracing and incorporating its narrative into present day uses of the site. Tryba’s research and the land-use maps she created will certainly help in this process when she publishes her master’s thesis, “PALIMPSEST: A Treatise to Preserve the Cultural Landscape Camp Kilmer on Livingston Campus,” in Spring 2018.