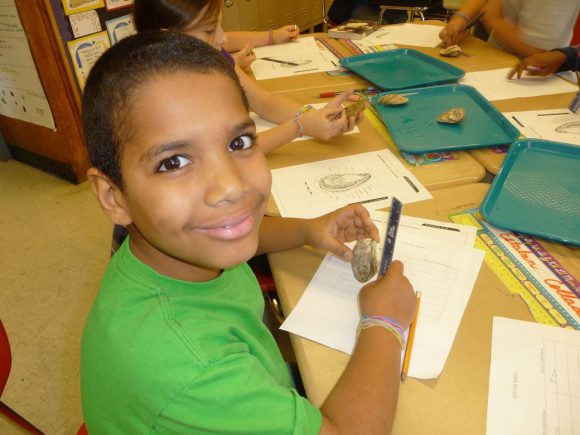

D’Ipolitto School fourth grader works through an oyster anatomy lesson.

Funny thing about oysters; once attached, you may be stuck on them for life!

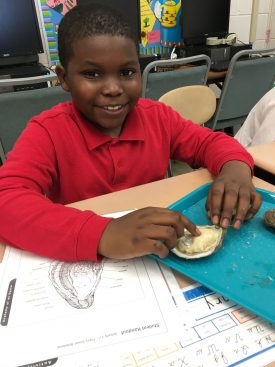

Friends from Max Leuchter Elementary School are working hard and having fun building shell bags for oyster restoration efforts in the Delaware Bay.

The excited fourth graders at D’Ippolito School in Vineland, New Jersey, raced across the school grounds to a small area beside the ball field where the surf clam shells were haphazardly stacked in a pile. Eagerly greeted by Rutgers University Haskin Shellfish Research Laboratory (HSRL) marine scientists Jenny Paterno, program coordinator, and Lisa Calvo, aquaculture extension program coordinator, who were ready to hand out mesh netting and gloves to the waiting students. It was time to get to work to create 500 bags of shell that would ultimately serve as founding structure for a real-world oyster restoration project. This proved to be a solid day’s work for the 100 students who worked like buzzing bees to get every single piece of shell into a bag.

For the past 10 years, this scene has become a spring ritual with hundreds of fourth graders rounding out the school year by working hand-in-hand with scientists through a community-based oyster restoration program known as Project PORTS: Promoting Oyster Restoration Through Schools. This unique program gives K-12 students an opportunity to experience environmental stewardship first hand as they help restore critical oyster habitat.

Developed and coordinated by the HSRL, Project PORTS utilizes the oyster as a vehicle to teach students, educators and the broader community about the bayshore environments and the methodologies and science of a real-world oyster restoration project.

Molly Calvo and Elly Thomas count shell bags deployed at an intertidal area in the lower Delaware Bay. The bags were relocated to the restoration site after oyster spat attached.

“The program is founded on the belief that stewardship grows from an underlying appreciation and understanding of the environment,” explains Calvo. And with Project PORTS, there is plenty of opportunity to learn.

Oyster reefs are arguably one of the most imperiled habitats on earth and oyster habitat restoration has become an important conservation goal worldwide. The Delaware Bayshore region stretches along the southwest coast of New Jersey and contains expansive coastal marshes, woodlands, beach habitats and many tidal rivers. It is widely recognized for its diverse wildlife and vast wetlands, and serves as a critical migratory stopover for shorebirds that feed on horseshoe crab eggs.

Here, the eastern oyster is recognized as a keystone estuarine organism because of its role in providing vital ecological services such as improving water quality, creating complex structural habitat and enhancing fisheries production. The oyster has also served as a principal Delaware Bay fishery, holding particular economic, social and cultural significance to communities along the Delaware Bayshore.

During the last century, dramatic declines in oyster production have occurred due to over-harvesting, disease, habitat loss and environmental change. Today, the Delaware Bay oyster fishery is carefully managed with a view toward resource and fishery sustainability. Large-scale habitat restoration efforts are underway to revitalize Delaware Bay oyster populations and ensure the economic survival of the oyster industry.

“The most effective means to restore oyster habitat is to provide oyster larvae with clean shell or cultch to set on, where the oysters glue themselves to the substrate and grow in that same spot the rest of their lives,” says Paterno. Created as oysters settle on top of each other, this reef structure provides habitat for scores of other organisms.

“The most effective means to restore oyster habitat is to provide oyster larvae with clean shell or cultch to set on, where the oysters glue themselves to the substrate and grow in that same spot the rest of their lives,” says Paterno. Created as oysters settle on top of each other, this reef structure provides habitat for scores of other organisms.

Since 2005, more than one million bushels of shells have been planted on historic or existing oyster beds within the Delaware Bay via regional efforts involving scientists, non-governmental organizations, government agencies and fishermen. Oyster habitat restoration efforts that once focused exclusively on rebuilding fisheries now also focus on ecological function.

Students from West Avenue School in Bridgeton display shell bag. The entire school participated in Project PORTS, providing an opportunity for older students to mentor the younger ones.

Although relatively small in scale, compared to these larger fishery efforts, the results of Project PORT’s restoration efforts are not insignificant. Thousands of student participants from 30 partner schools have constructed over 29,000 shell bags that have become a settlement surface and home for more than 30 million young oysters.

The Project PORTS reef, currently off limits to harvest, was primarily built to support bay health and ecology. Located in the Delaware Bay off Gandy’s Beach in Cumberland County, it encompasses five acres and, for the past two years, has also served as part of the living shorelines project that seeks to rebuild area beaches destroyed by Hurricane Sandy. The living shoreline effort is a collaborative initiative led by The Nature Conservancy, and supported by the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

But, the main objective of Project PORTS is not to build oyster reefs but to create an excitement for science, an appreciation for the Delaware Bay and to instill stewardship values, stress both Calvo and Paterno.

Students participating in Project PORTS become junior oyster experts.

Long before students don their work gloves and begin filling bags from the large shell pile on the beach, they are already junior oyster experts. Through in-class lessons taught by Rutgers scientists prior to this culminating activity, the students have dissected oysters, created hypotheses, run experiments to demonstrate oyster feeding and constructed oyster fishery focused timelines. Altogether, Project PORT’s rich curriculum guide offers more than 20 classroom ready lessons that have proven to excite students while meeting national science education standards.

Recently added lessons focus on the diversity and richness of species on and around the Project PORTS oyster reef that was started 10 years ago. Paterno, a recent graduate of Rutgers ecology and evolutionary master’s degree program, developed this particular activity using authentic data generated as part of her thesis research. The study focused on evaluating the ecological services of the small-scale Project PORTS reef relative to natural oyster reefs.

“The outcome was exciting as the research demonstrated that a viable, multi-generational oyster population has been established at the area and the restored reef supports species diversity, abundance and richness on par with the natural reefs,” explains Paterno. “This shows that the restored reef is functioning well and contributing to the ecological health of the Bay.”

Maggie Elgin, a Project PORTS participant.

Through the program’s holistic, experiential approach, students become more environmentally aware, literate and engaged. Assessments completed by students participating in Project PORTS over the past several years routinely show greater than 100% increases in average assessment score demonstrating significant gains in knowledge and understanding of ecosystem complexity.

“For many of the students, it is the first time they have the opportunity to see, firsthand, the environment that many of us [local adults] take for granted. To see the excitement on the faces of many students is something to behold,” says Sean Fallon, teacher at West Avenue School, Bridgeton, NJ.

Molly Calvo (right) and Elly Thomas (center) working on oyster farm with co-worker Diane Driessen. Molly and Elly, now college majors in environmental science and engineering, received their first introduction to the bay through Project PORTS.

As Project PORTS celebrates its 10th anniversary, Calvo reflects on the time that “passed way too fast.” She notes that the very first cohort of students that participated in PORTS is now college age, like Maggie Elgin, who came out with her grandfather to help deploy shell bags at the age of eight. Maggie, now a college student at the University of California majoring in marine biology and environmental science, recently wrote to let Calvo know how much Project PORTS had inspired her, adding that she was considering a summer internship working with oyster restoration in the Chesapeake Bay.

Calvo also fondly remembers Elly and Molly covered with mud after working on an oyster farm. They too had their first Bay experience through Project PORTS.

Funny thing about oysters; once attached, you may be stuck on them for life.

5th grade students from Max Leuchter Elementary School and their teacher proudly show off the shell bags they constructed during a Project PORTS program.

Friends School Mullica Hill students create a bucket brigade to transfer shell bags from truck to beach.

Students from Arthur P. Schalick High School’s (Elmer, NJ) marine science class celebrate after using shell bags to construct a new oyster reef on Gandy’s Beach.

A 4th grade student from D’Ippolito Elementary School in Vineland, NJ smiles as he examines an oyster for the first time!

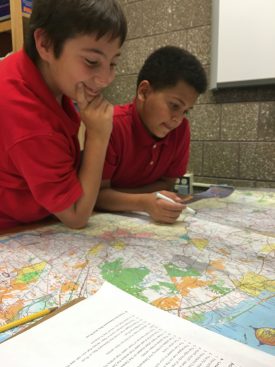

Follow that river! 5th grade students from Dr. William Mennies Elementary School in Vineland, NJ work through Project PORTS’ mapping scavenger hunt activity.

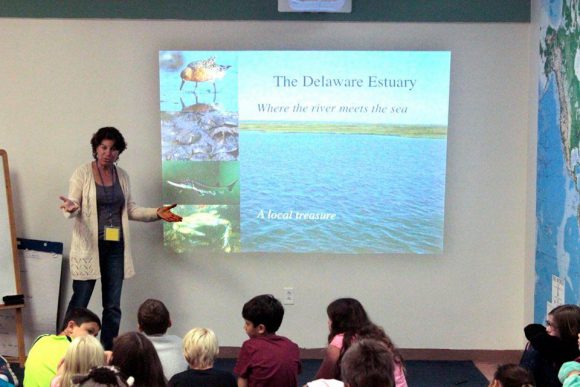

Project PORTS program coordinator, Lisa Calvo, speaks with students in Wilmington, DE, about the importance of oysters and the Delaware Estuary before they dive into an oyster dissection activity.