Bonnie McCay on the coast of La Jolla California.

By Samuel Ludescher (SAS’18).

To understand what “the commons” is and the importance of maintaining it, first recognize the commons as a general term describing any system where the resources are used and perhaps owned jointly, in common, rather than separately and in private. The term was popularized by Garett Hardin’s 1968 article, “Tragedy of the Commons,” depicting a hypothetical village where herdsmen shared a common grazing pasture. The herdsmen were enticed to increase their herd without limit and allow their animals to graze freely due to the unrestricted nature of the pasture. Left uncontrolled, the quality of the pasture declined.

“It is the ‘why not, someone else has done it’ sort of psychology,” says Bonnie McCay, now retired Rutgers Board of Governors Distinguished Professor in the Department of Human Ecology. The quality of fishery commons has declined in a similar fashion, ecologically and economically, according to McCay. The commons as a concept can be applied to all manner of ecological resources, such as nature conservancy, which is exactly why her research is so transferrable.

Bonnie McCay with a fresh catch in Newfoundland Canada.

McCay grew up in Southern California. She loved the beach and always wanted to work near the ocean. Fishing did not occupy her youth, though it would occupy her research later on; but, her father fished for fun. While a doctoral student in anthropology at Columbia University, McCay traveled to Newfoundland one summer to explore possibilities for her Ph.D. research by the ocean. Fishing was the main activity and source of livelihood in Newfoundland, however, McCay still found it rather difficult to discover a research topic. She was stuck on the highway one day due to construction and was listening to the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation on the radio to keep from being bored. An interview with a fishery economist was being aired, describing what he called a “tragedy of the commons,” identifying the “open access” or relative freedom people had to compete with local fisheries as a reason for poverty in the fishing ports of Newfoundland. Right then and there, McCay found inspiration for her doctoral research, which centered on the question of the commons and the notion of ecological and social resilience in coastal communities.

Two pertinent challenges present themselves when attempting to maintain fisheries or any other common-property resource. Firstly, “exclusion of potential users” is problematic. The physical nature of the resource is such that controlling the access of potential users is costly and, in some cases, virtually impossible” (B. McCay, D. Feeny, F. Berkes, J. Acheson 1989). Secondly, a characteristic of common-property is subtractability. If there is no established quota or enforced governance, nothing is stopping one fishery from taking the potential shares of another.

The United Nations Law of the Sea Conference attempted to address these challenges, establishing a 200-mile exclusive fishery zone in 1977 that granted control of coastal waters to the respective nations. The U.S. has its own, so does Mexico and Canada, and so on. McCay has conducted research on how to better control the competition that takes place within the 200-mile zones of Mexico, the U.S. and Norway; also, Newfoundland, Canada, where she conducted work for her Ph.D.

McCay’s research evolved from focusing on ecological and social resilience into a critique of the tragedy of the commons theory, identifying methods of resource management that empower local users of the commons to foster economic and sociological growth for local regions. The two solutions advocated by many, including Hardin, are top-down government control or, on the other hand, privatization, letting market forces and the incentives of ownership be controlling factors. McCay and her colleagues have argued that both approaches have often serious repercussions for communities, and that communities of users can often develop the capacity to manage common resources on their own. They may do this in concert with government, in “co-management” arrangements; they may do it exerting some degrees of privatization, as in various forms of localized enclosures; or they may do it on their own through community-based management.

“We do rely on government in managing the commons. That is only part of the story. If you don’t have people that use the resource engage in this process, then it will not be successful,” said McCay. Therefore, privatization has become popular among coastal fishing communities.

Market-oriented privatization, while considered by McCay to be detrimental to local communities, is still heavily utilized and “grants each resource user, say fisherman, exclusive marketable rights. Each boat owner is given a share of the fishery in a percentage of the quota. Say, only 10,000 pounds can be taken each year to sustain the fishery. These quotas can be bought and sold,” said McCay, who has researched this form of privatization in the sea clam fisheries off the coasts of New Jersey and neighboring states.

“Fewer people amass more of the quota. Others do not. This system is promoted worldwide. The idea is to reward efficient business. The criticism is that it creates an emergence of a ‘Wal-Mart’ and threatens small-scale fishing communities and enterprises. That is why the idea is very controversial,” said McCay. Just as multinational corporations like Wal-Mart control large portions of retail markets, industrial fisheries threaten to overtake local fisheries and destroy coastal economies. “This is why people are looking more at community-based systems. Relying on the market disadvantages smaller scale businesses.”

An alternative, community-oriented privatization approach is sociologically different, relying on local governance and community ownership to both promote exclusion and diminish subtractability. Users take only what they need so that they can continue to use the commons. This approach birthed the ideas of co-management and community-based management.

“There is a universal need to balance large industrial businesses against the needs of those that depend on fishing as a livelihood,” said McCay.

A shining example of community-oriented privatization was identified through McCay’s research in Mexico’s Pacífico Norte, located close to Baja California. Following historical ecological problems that arose in the region such as encroachment by foreign fishing companies and declining fishing stocks due to a drastic change in water conditions, the Mexican government threatened to close local fisheries unless they committed to taking on greater responsibility for sustaining and cooperatively managing the fishery.

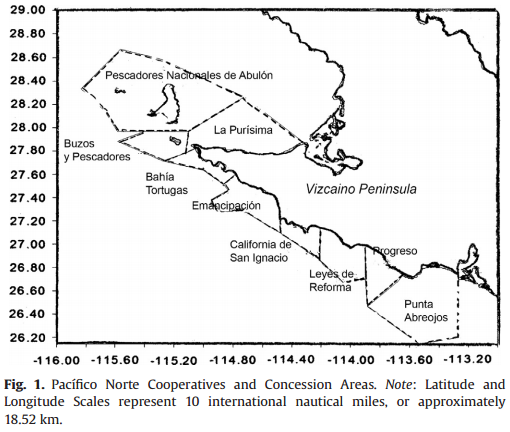

Visual aid of fishing concessions in Mexico’s Pacífico Norte.

This challenge was met by existing fishing cooperatives, which are democratic, community-based business associations in which the fishermen are the owners. In the Mexican case studied, “cooperatives are part of a federation (FEDECOOP), which helps them relate to government and the markets. It also helps them coordinate their fisheries, aided by their geographic proximity, side-by-side along the coast” (McCay et al., 2013). Each cooperative is granted exclusive rights to fish specific species of fish and shellfish in a given area, known as a concession. A concession is granted for several years and must be renewed periodically to maintain the cooperative’s exclusive rights. The cooperatives have been able to achieve very profitable and ecologically sustainable lobster fisheries based on their capacity to manage the fisheries within their concessions. This is done in conjunction with other cooperatives (within a federation) and government agencies. There is now a strong relationship between government and local fisheries in Mexico’s Pacífico Norte. Mexico has provided a strong example of successful community-based management and co-management, enabled by privatization at the level of the concession.

“Since 1999 the concept [of co-management] has taken root around the world, more and more cooperative management exists,” said McCay.

“Beyond fisheries, cooperative management has become a very important part of wildlife management in Africa and forest life management in India. People who live in a village region are regaining the rights to manage their own resources. Colonial powers took control over them and their resources and then national governments claimed control after colonial powers left,” said McCay. “There has been a movement focused on local control and enforcing the rules on outsiders. Some in local areas are working closely with governments to create laws to manage their natural resources, such as in the Philippines.”

It seems contradictory to privatize a common-property resource and grant exclusive rights to a small number of users. But, these rights are prescribed with responsibility on the premise of sustainability. Exclusion is encouraged only to ensure that the resource may flourish to meet the needs of many for future generations, instead of allowing the market to take what it wants until there is nothing left. One fiscal year is not worth a lifetime of sustenance.

McCay was the first woman to receive the American Fisheries Society’s Award of Excellence, which she did in 2013. She was also a recipient of the 2015 Ostrom award—named for Nobel-Prize winning political scientist, Elinor Ostrom—given by the International Association for the Study of the Commons. McCay followed in Elinor Ostrom’s footsteps when she accepted an invitation into the National Academy of Sciences in 2012.

Her book “The Question of the Commons” was a driving force in the inception of the IASC. Academics, practitioners, and those involved with NGO’s as well as private citizens and members of watershed associations gather for the IASC’s bi-annual conferences to “work on the challenges of governing whatever they see as their commons: fisheries, water quality, and so on. They try to have both researchers and practitioners present at these conferences,” said McCay. Initially a US based group, the IASC has grown internationally. McCay has gone to every conference since its creation in 1987. The IASC has been funded by major philanthropic organizations such as the Rockefeller Brothers Fund and the Ford Foundation.

McCay has written many scientific papers on the commons and published three books: “The Question of the Commons,” 1987; “Oyster Wars and the Public Trust: Property, Law, and Ecology in New Jersey History,” 1998; and “Enclosing the Commons: Individual Transferable Quotas in the Nova Scotia Fishery,” 2002. While a tenured professor at Rutgers, McCay taught in the Department of Human Ecology, serving the major in Environmental Policy, Institutions, and Behavior. She retired in 2015.