William Sansalone (Ag’53, GSNB’61). Photo courtesy of Georgetown University Medical Center 2007.

“After a 46-year career in urban medical centers, I remain a farm boy at heart,” wrote Bill Sansalone, Ph.D., in a thank-you note he sent after receiving a packet of the Rutgers 250 tomato seeds as a gift.

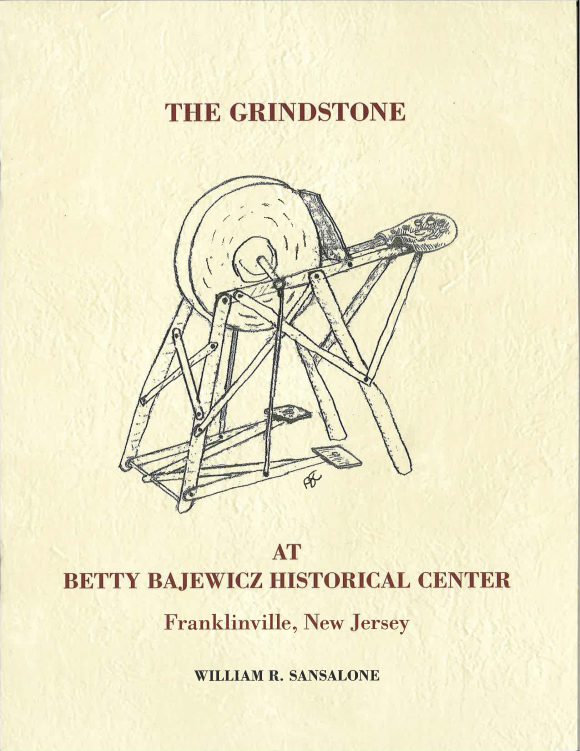

Enormously appreciative of his roots in south Jersey agriculture, Bill has gone to great lengths to stay in touch with his heritage and to celebrate it. One of his proudest accomplishments this past year was the creation of a 24-page brochure, “The Grindstone at Betty Bajewicz Historical Center,” which chronicles the discovery and restoration of his parents’ grindstone from their former homestead in Malaga, New Jersey, and the remarkable significance of a seemingly ordinary piece of equipment to farm life in a bygone era.

Because farming in the nation’s early history consisted of heavy hand labor using tools that required regular sharpening and honing, the grindstone played an important role in agriculture. Bill Sansalone became engrossed in the subject in 2006 after a visit to his boyhood home on Dutch Mill Road in Malaga. There he found the abandoned grindstone that his parents relied on for working the farm, and he felt its connection to them – “What I saw was a priceless piece of family history that had to be rescued.”

Rescue it he did with the help of two nephews, Fred and Mike Schiavone, who acquired and rebuilt it for display at the Betty Bajewicz Historical Center in Franklinville, New Jersey.

Bill’s parents, Fortunato and Rosa Sansalone (they anglicized their first names to Fred and Rose), emigrated to the United States from Italy in 1913, seeking a better life. According to Bill’s “Grindstone” brochure, in 1916 they bought 20 acres of woodland three years later in the Malaga section of Franklin Township in Gloucester County and moved into an old frame house on the property.

The Sansalone parents cleared their land of the white oaks by hand, using axes, mauls and pickaxes that were maintained with the grindstone. They grew corn and hay to feed their livestock and cultivated field crops that were shipped from a local freight rail stop to Philadelphia and New York City.

In terms of acreage (eventually 35 acres total) their farm was small, but the family cultivated it intensively, Bill recalls. Farming is a seven-days-a-week, 365-days-a-year proposition, so Bill was well accustomed to working hard. One of his favorite diversions was listening, along with his father, to the advice of the Rutgers Cooperative Extension agricultural agent, who would visit the farm and who “had a huge impact on the farm operation,” he says. “George Lamb was an exemplary county agent. To me, he represented Rutgers.” Lamb’s influence prompted Bill to select Rutgers “as my first and only choice of where I wanted to go to college.”

He also was swayed by the week he stayed on the Cook/Douglass Campus as a representative from his high school at Boys State in the summer of 1948. The boys were housed on the Douglass Campus and ate in the old Cooper Dining Hall. Each morning they participated in a flag-raising ceremony on a triangle of grass on Lipman Drive.

“This gave me the opportunity to see the ag campus and also to meet Professor Frank Helyar, a person of great stature on the campus.” Helyar interviewed Bill, “and apparently he was impressed because I got admitted. I also was fortunate enough to get a rare gem – a state scholarship that paid my full tuition, which at that time was nine dollars a credit hour.”

He decided to major in agricultural education – preparing himself for a lifelong dream of becoming a vocational agriculture teacher. “I had to make a decision as to whether to pursue plant science or animal science. I chose the latter because my hometown was in a poultry and dairy area, and I planned to teach close to home.”

The Korean War intervened, however, and as an Air Force ROTC student, Bill was commissioned as a second lieutenant upon graduation and got orders to report for active duty. Just days later, though, his orders were canceled and he was told to stand by.

Hearing nothing about his active duty for several months, he trekked up to New Brunswick to find out if the ROTC office had any information about his status. It didn’t. But he happened to run into Professor Spencer Davis, who had been the faculty advisor when Bill was living in the Alpha Gamma Rho fraternity house.

“Professor Davis was collaborating with the University of New Hampshire, which was looking for a research assistant in animal science for a Monsanto Fellowship. One call to New Hampshire by Davis, and I was accepted sight unseen. So I started work on my master’s degree there in animal nutrition, which had the added benefit of deferring my active duty until 1955.”

After receiving his M.S., he began his military obligation, serving two years in Germany. His sister-in-law, the wife of his oldest brother and a kind of second mother to Bill, kept him close to the home front with frequent letters while he was away. That connection became significant a few years later in Bill’s life.

“I served in Germany for two years, and when I got back in the late 1950s, I was astonished to find that most of the vocational ag teaching programs in the local high schools had been discontinued. So there I was all dressed up with nowhere to go.”

The image of the grindstone on the cover of Bill’s brochure was sketched by his late wife, Alice Koury Sansalone. Click on the cover image for an excerpt from his brochure, “The Grindstone at Betty Bajewicz Historical Center.” For more information about the brochure, contact the author at ws31@verizon.net.

Trying to decide what to do next, Rutgers once again entered his life when he connected with Professor James B. Allison of Rutgers College who was well known for his Bureau of Biological Research and for his collaborative research with several pharmaceutical firms. “I began work on my doctorate in nutritional biochemistry and received my Ph.D. in 1961. Thanks to the university’s fine reputation in biological research, I was able to obtain a faculty appointment at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn,” Bill says. He served at Downstate for 10 years as an assistant professor and then a tenured associate professor in biochemistry.

After SUNY, Bill went to the Washington, D.C. area, where he worked for the National Institutes of Health for 25 years. He finished his career in 2007 as associate director for research development with Georgetown University Medical Center. There, he advised faculty members on funding sources and developing research proposals and simultaneously served as adjunct professor of biochemistry. In 2000, Who’s Who in America included Bill’s name in recognition of his societal contributions over many years.

In retirement, Bill stays connected with Rutgers by visiting periodically (he still has family in New Jersey) and by donating regularly to the Ruth Pease Sansalone award for students involved in the Office of Agriculture and Urban Programs.

You see, Ruth Pease Sansalone was the sister-in-law who kept in touch with Bill when he was away from home. When he returned from military service in Germany, he had saved $2,000, a princely sum in 1958. Ruth, who was only in her 40s, died of pancreatic cancer shortly afterward. He took $1,000 – half of his savings – and created a gift in her name, a gift that he supplements from time to time even to this day.