[Editor’s Note: In the spring 2015 issue of the SEBS magazine Explorations, the 1963 alumni class correspondent shared Phillip Gordon’s recollection about living on the Douglass campus, a blizzard and eating with the young women of Douglass at the Douglass College dining hall – punctuating the tale with “What a misfortune!” Phillip contacted us to correct some of the facts in the story. Below is the corrected version and much more of Phillip’s story.]

“While it was nice to see the mention on the ‘Alumni Notes and Musing’ page, it was not entirely accurate,” wrote alumnus Phillip Gordon. “Population growth at Rutgers College in the late 1950s and early 1960s led to a severe housing shortage. I spent my 1959-60 freshman year in the basement of, I believe, Leupp, in what was a barracks-like set–up with an open space, beds, and metal storage cabinets.

[Note: Leupp Hall, built in 1929, is still a student residence on the College Avenue campus, with single and double rooms – no barracks, thankfully.]

“My 1960-61 sophomore year, they housed some of us on the Douglass campus, in one of two groups of small buildings [the Corwin Houses] that served as some of the Douglass dorms. During a blizzard, for one night, they opened the Douglass dining hall to us because we were stranded. Food deliveries to New Brunswick were mostly stopped, and College Avenue was impassable.”

With the story corrected, we asked Phillip to tell us more about what he recalled from that era and what he is doing now.

Phillip has some great memories of his time at Rutgers and the influence it had on his life and overall outlook. For instance, he actively participates in the sport of fencing, a pursuit he discovered while at school. “I had never participated in organized sports,” he recalled.

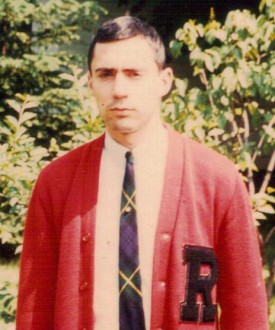

“Early in my freshman year I saw, in the student union, a badly mimeographed poster with an outline of a fencer and saying, ‘Fencing – No Experience Necessary.’ I am still not sure why I went, but I fenced for four years, and because the team manager gave me my equipment when I graduated, I kept it up and, 55 years later, I am still at it.”

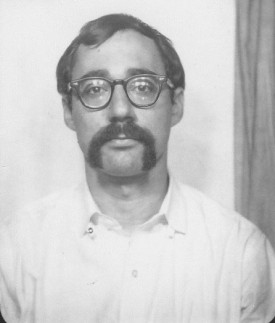

A photo from 1991 shows Phillip with an epee, which along with the foil and the saber, are the three weapons used in fencing. “I was started at the RU fencing team in foil (as most people are started in fencing), but in the first meet my freshman year was shoved in at epee,” he recalled. He speculates that the coach made the switch so Phillip would fill out the team, “because teams won college meets by winning more bouts in all three weapons. I asked the coach ‘What do I do?’ since I had never held an epee. He said, ‘Hold out your arm.’ I was fencing a kid much shorter than me, and he ran onto the point five times, so I won. And that’s how I ended up fencing epee for 55 years.”

Among the other memories is a Douglass College art history professor who taught High Renaissance Art at the time and was so influential that Phillip actually considered changing his major in his junior year to art history. “She was an intense woman who chain smoked in the class,” he recalled. “Those were different times, obviously.” Another quirky professor – this one teaching psychology – used to enter through the window of his below-ground classroom. “He was the first one I ever heard say the definition of insanity was seeing a psychiatrist. He had worked in a mental hospital.”

Then there was the lasting impression left by William H. Martin, dean of the College of Agriculture during Phillip’s first year. “He had just come back from the Soviet Union, as it was called then, and told us things that, even in 1959, prefigured the fall of that country. In the mid-20th century they hardly used tractors in agriculture, missing out on one of the major technological and productivity advances.” Martin was an icon in agriculture, both in the U.S. and internationally. He became dean of the College of Agriculture and director of the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station in 1939 and retired in 1960, succeeded by Leland G. Merrill, Jr.

A resident of Castro Valley, Calif., across from San Francisco and the Silicon Valley peninsula, Phillip has retired from what could be described as an eclectic career.

Having grown up mostly in Queens, N.Y., he chose Rutgers because “my dad went there (RC ’32) and because, at the time,” he said facetiously, “they let in a few sons of alums even with bad high school records.” When he came to Rutgers, he was “in love with biology” and planned to become a veterinarian. “Then I found that being fascinated by nature and animals was not what attracted me to biology, but in fact, genetics. So I trained as a geneticist, although I never used it. Instead, I became a biology writer and then, by accident, in California, a technical writer of computer manuals just at the time when computers were being turned into PCs, and rode that wave.”

He gravitated to the corporate world in financial services, “helping people use and apply PCs to business, then eventually doing some teaching in business schools” – Haas School of Business at the University of California-Berkeley, the Norwegian School of Management, and finally the Lokey Graduate School of Business at Mills College in Oakland, Calif., where he taught for eight years. “I am still a gadget lover, having been around for the birth of PCs, cell phones, and the Internet,” he said, which is an amazing reflection of the vast leap the world has made in just a few decades.

Phillip went on to earn a master’s degree in zoology from Rutgers-Newark and holds a Candidate of Philosophy in genetics from UC-Berkeley. He has been back to the New Brunswick campus only once since his graduation, but stays in touch with two special classmates: his wife (DC ’65) and his brother, Andrew Gordon (RC ’65).

And by the way, getting back to the blizzard-y day at the Douglass dining hall, Phillip recalled: “The dining hall – I don’t remember where it was, but we walked there from Corwin – seated all the guys together at tables, but other tables had women, so we weren’t really separated.” No misfortune there.